In the vein of keeping old-time music, alive let’s talk about your role in Ken Burns’ new documentary, Country Music.

I’m so proud to be a part of the film. He’s been making it for eight years and it’s 16 hours long. He conducted about 140 interviews, and 40 or 50 of them were with people who are now gone from this earth. So I think that it was really well timed, to capture the real heart of the music, because there’s never going to be anyone in country music like Little Jimmy Dickens, for example. Nor is there ever gonna be another George Jones. So, the fact that we get to see them, as moviegoers… Merle’s gonna whisper something into your ears, too. It’s gonna happen, and it’s gonna be all ever-loving powerful. Merle is like the bard of the tale that Ken is telling. Ken leans heavily on Merle at any moment that the script needs a preacher.

I went up to New Hampshire, where the film company Florentine Films is, and I was an early advisor to the film. I read through scripts, conducted an interview, and Ken, the two other producers of the film and I went on tour together around Tennessee, drumming up publicity for the movie. It’s been really fun getting to know Ken. I grew up in the Shenandoah Valley, where everything—every high school, every cul-de-sac, every shopping center—was named for a battle, a general or some other dead man. It was all named for the war. And yet, nobody was talking about the war. When they talked about a general, it meant where you could go and buy, like, a stereo—the name of a mall. I was 11 when The Civil War came out—Ken Burns really gave me the tour of my own backyard. And for four weeks or something, I was able to watch that whole series. And it really brought alive in me a passion for the sort of crossroads of history and soul. This feeling that, “Oh, they’re not dead.” It just changed. The echoes of the war were still so present in the valley—not just in the names of the cul-de-sacs, but in the racial politics of the state. You know, Governor Douglas Wilder was the first black man elected governor of any state, and it happened in Virginia in 1986, when I was a kid, just a couple years before the movie came out. Seeing the response to that—in racial violence in my community—and just knowing that the cost of the war has not yet been paid, it made it feel really important to me to do something to help pay it, knowing that everybody shouldered the burden. The burden didn’t end with the armistice.

When you got involved with the new documentary, did you hope that it would have that same kind of effect, teaching people that history and keeping those names alive?

Yeah. I am hoping that, when the film comes out, a kind of reckoning can take place, because a lot of the labor that goes into the creation of country music, and the stewardship and maintaining country music, is a sacrificial one. There’s a lot of people who have been left out of the story, or were denied access, systematically, throughout time. There have been stories that have gone unspoken, and that’s why it’s so important to have the outsider perspective. Ken is an insider-outsider—he is America’s most beloved documentarian, and he can talk about whatever he deems American. But Nashville music has always had the desire to talk about itself, and country music is built on this concept of nostalgia and collective memory, because we seek to retell our story all the time. I’m sure if you turned on the radio today, you’d hear at least a handful of songs about the old days. And what the old days are in 2019 are different than what the old days are in 1923, when they were still singing about the old days. But it’s important that the outsider come and appear and tell our story—because we’re all gummed up in the works. Nashville can’t tell its armpit from its ass. We’re all just swimming in the stuff, and Ken Burns is like a chopper, high above.

You mentioned people who have been passed over in the story of country music. Are there any names in particular that the new documentary highlights that music fans should know about?

I think all lovers of American music should know the story of DeFord Bailey, and yet we don’t. Not because it wasn’t a story heralded in its time, but you can’t dig up your great-great-grandfather and ask him. Thankfully, this documentary sets the record straight about DeFord. It really works to reset the context of country music as a part of black music expression of the 19th and early 20th centuries. You know, why did Bill Monroe sound so good? Because he learned to play from a black man. And even though there’s no part of Bill Monroe’s career that you can point to and say, “This is the black period,” or, “Look, there he is with Ray Charles.” That doesn’t exist. But, you watch this film and you can see—without Louis Armstrong, there is no Bob Wills.

But it’s one thing to have it on the screen; it’s much more important to pay it forward. For example, I judged this fiddle contest this weekend at the Country Music Hall of Fame. This was a contest started by Roy Acuff, the Grand Master Fiddler Championship. It’s really sparsely attended—everyone’s comin’ in from out of town, and there are lots of young kids. This was contest fiddling—oftentimes its virtuosic, but it’s missing the performative nature of music. Anyway, they gave me 20 minutes just to do a little talk and play some, and I was quick to be sure to play some music out of the black fiddling tradition. It’s moments like that when I feel like there’s work that I can do in collaboration with the film. Because it’s one thing to have it up there on the screen and be like, “OK, it’s done. Everything is set.” It’s not done. It’ll be done when the CMA board is a diverse board that looks like America. When the roster of top-ten records on the radio has a whole lot of women and a whole lot of people of color. Because women and people of color have just as much authority in country music, just as much invention, they just don’t have it in their name. And I think the movie can help us move forward.

Shifting to Old Crow’s new live album, recorded at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium. What was the impetus behind this release? Was there a similar connection to honoring the past with some of the songs the band selected for the setlist, like “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?”?

I think our desire to put the record out had a lot to do with the Ken Burns film, to be able to do a further embrace of the movie by letting an audience know: Here’s this band that has asked itself the question, “Will the circle be unbroken?” for the past 21 years, and has done its best in the spaces of country music to ask that question. The Ryman looms very large in the collective heart of country music fans. We’re a band that’s had this really special privilege of being able to be something of a house band in it. The Ryman, like country music as a whole, is a place that collects a whole lot of very different roots, all into one tree.

And then you look at the fact that this place was built because of a divine decree. This guy, Tom Ryman, he’s a riverboat captain; he spends all his money on prostitutes, he makes a lot of money and he’s got to come clean. He goes to a tent revival and sees this preacher, Sam Jones, the most popular preacher in the South, and he gets a visitation from God that says, “Tom Ryman, build me a Tabernacle, and built it for all people.” So Tom built the Union Gospel Tabernacle, in the Confederacy. This is in the 1890s, so the echoes of the war, they’re right there. This generation of black statesmen have just been exiled from leadership. And yet, he doesn’t build the Confederate Tabernacle, or the Southern Dixiecratic Hall, or anything—he builds the Union Gospel Tabernacle, a house of worship for people downtown. It’s not out by Vanderbilt, not out by Belle Meade; it’s right downtown. And then he dies, but the place fills up with Charlie Chaplin and Bert Williams and Jenny Lind and Martin Luther King and DeFord Bailey and Roy Acuff. I just think that the Ryman is such a good example of the institution of country music, of how enriched it is by the offerings of so many cultures. I mean, I’m not a historian or a musicologist; I’m a performer. Not a conjurer or anything else—or a politician—but I know that, as a performer, our music does better in the company of all of the ghosts of music past. Music has some sort of cellular thing where it gloms onto all of the other sounds. And when you play in places that are spooky like that, then your music just gets richer. It’s like, you wouldn’t want to lick the walls in the Ryman, because your head would spin. [Laughs.]

With this documentary, the Ryman album coming out, playing with Bob and thinking about all that—that headspace you’re in—do you see that affecting Old Crow going forward? After two decades, what do you see as the next chapter of Old Crow Medicine Show?

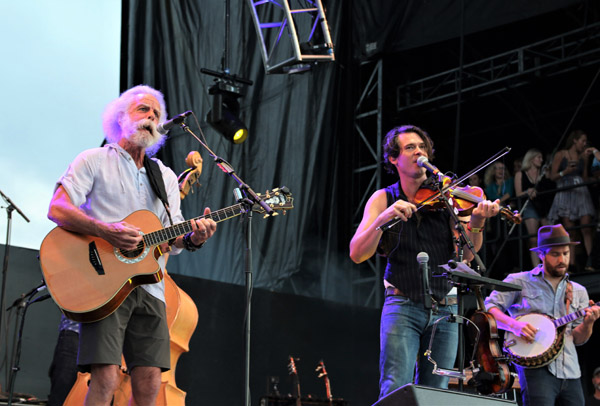

This might be a bit of a diversion from that question, but one thing that I think could bring it all full circle would be for country music to take a good look at the Grateful Dead. What is the country music part of the story of Bob and Jerry and the guys? Because it’s obvious to me—and it’s not just the pedal-steel part on “Brokedown Palace.” There’s so many intersections of the music of the Grateful Dead and country music roots. I mean, clearly, Bob loved Marty Robbins—even sings like him sometimes. Or, looking at Old & In the Way and taking a more musicological approach to it. One of my favorite players in Nashville is a 90-year-old mandolin player named Jesse McReynolds. Periodically, we’ll sing together on the Grand Ole Opry, and I’ve been over to his house. He loves to do that—he even made a Grateful Dead tribute record when he was like 87. He played with The Doors, and he remembers Jerry arriving on the pilgrimage to meet him. I’d love to see country music be so wide in its reflection that it’s able to see and acknowledge the efforts from the hippies of San Francisco. Frankly, they’ve had a lot to do with it. In some ways, the film tackles this—not with the Dead, but with The Byrds. That makes sense—it’s a little more of a leap to talk about the Dead with country. But I can see the day coming when there would be some tie-dyes hanging down there at the country music hall of fame. And I’d like to be the guy to pin them up on the wall.

1 Comment comments associated with this post

Raising the Dead: Ketch Secor Talks Old Crow Medicine Show’s Live at The Ryman, Ken Burns’ ‘Country Music’ and Playing with Bob Weir – jambands.com | Prometheism Transhumanism Post Humanism

October 8, 2019 at 4:43 pm[…] Read the rest here: Raising the Dead: Ketch Secor Talks Old Crow Medicine Show's Live at The Ryman, Ken Burns' 'Country … […]