This Friday, Oct. 4, Old Crow Medicine Show will release their new album, Live at The Ryman, which captures various cuts from the country-folk stalwarts’ many performances at the famed Ryman Auditorium in Nashville over the past half-decade. Ever the torchbearers of down-home, old-timey, harmony-filled music, Old Crow have ridden the wave of the 21st-century folk-revival to awards and accolades over the years, but the group’s founders haven’t forgotten the musical and geographical roots that spawned their success.

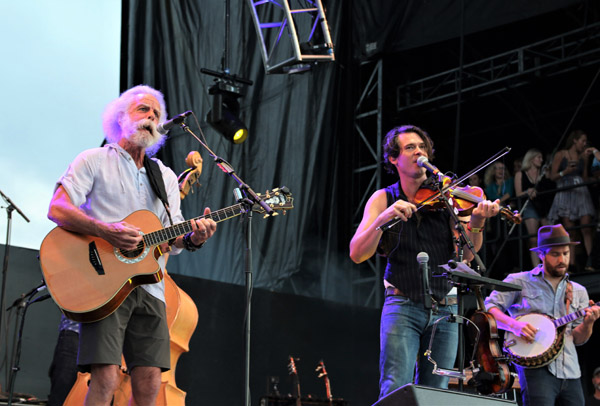

Old Crow co-founder Ketch Secor recently helped with the creation of Ken Burns’ newest documentary, Country Music, which chronicles the myriad stories—both well-known and nearly forgotten—that have shaped the history of the genre for over a century. Here, Secor talks about keeping the memory of country, folk and bluegrass music alive through the documentary and in his own music and actions, plus his recent experience with playing alongside Grateful Dead guitarist Bob Weir at LOCKN’ Festival in Old Crow’s home state of Virginia (where they collaborated on “Mexicali Blues,” “Cumberland Blues” and “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?”) and why Old Crow Medicine Show might have a bit more jamband in them than they previously thought.

Let’s start with this year’s LOCKN’ Festival, specifically your set and the Bob Weir sit in—how did that come together?

Bob’s people reached out a few days ahead of our tour and let it be known that he was interested in sitting in with us, asking what we would play. So we sent him back a list of tunes, and he picked the ones that we played from that list. Then we warmed up in the trailer and we hit the stage together. There are just a few moments like that in the life of a musician, where it seems that some sort of spiritual butterfly will land on the headstock of your guitar and just flap its wings. It reminds you of where you came from, where the music came from, and lets you know you’re not alone and that your dreams are coming true, all at the very moment of your singing.

Did you grow up with the Dead? How would a younger version of Ketch have viewed that experience, being onstage with Bob Weir?

Well, it would have been unfathomable to me as a younger person—that the person I was looking at, with eyes strained through an LSD hit, was going to be, like, a friend on the stage, years later. I saw the Grateful Dead at Giants Stadium the summer that Jerry died. It was mid-June, in the burning-hot Meadowlands of New Jersey. I think that, if I wasn’t 16 in 1994, I probably would have been to a lot more Dead shows—but I just got to go to the one. I loved the music, and I’ve always felt that our band was part of the same family—we were just a little further down the line. Also, so much of our influence tended toward the earlier side of the Grateful Dead, so it sort of felt like, well, maybe it’s more of a horseshoe shape?

Had you played with any of the members of the Dead before?

Well, we worked some shows with Phil [Lesh] this summer, but in the capacity of Willie Nelson [on the Outlaw Music Festival Tour], so I don’t think Phil knew us, but he did watch our sets most nights—just awesome to have him there. And then there was some correspondence a long time ago with Billy Kreutzmann that nothing ever came of.

But the thing is, when someone is your hero, they take on a life in your life that is not their life, but something related to your own imagination and dreamscape. And then there’s this positively charged sonic landscape in which Jerry lives forever, and Pigpen never died, and they’re taking their first banjo lessons, and they’re learning to sing folk songs in the early 1960s, all in the same breath as singing “Cats Under The Stars,” and death and beyond. That’s the kinship that I think the Grateful Dead embodies better than any other music maker. The immortality piece.

And the relationship of the music to a spiritual plane doesn’t need to be a particular spirit; you can put any deity you want in that picture. That part’s not very important to me. Chuck Berry did the same thing—he lives forever—but he didn’t talk about living forever, and he didn’t dance about living forever. If he did, he did it in subtle ways. The Dead invited you into a world that very much was stated as a spiritual plane. The music undulates and moves like the soul.

Do you aim at something like that with your own music?

No, man, I’m a revivalist. I’m just trying to raise the dead—I’m not trying to coexist with them.

How did you pick what songs you wanted to play with Bobby?

Well, I hope to check the list again sometime and get to pick again, because there’s a lot on that list. Our band has always played Grateful Dead music; we grew up on Grateful Dead music. I polled the band, because we’re all such big fans, so it was so easy to get a list of twenty tunes together. Most of them we had not played before, but we had a few regular songs in our rotation, and certainly a lot of common ground. What’s interesting, I think, for our collaboration is that we’re really from the roots-music world, like the Dead, but we’re not at all from the jamband world, so our crossroads happens in a very less-than-obvious place, in a really deep and soulful place. I think that, when we started singing together with Bobby, it instantly felt locked in.

There’s so many people [at festivals] you might want to meet, but these [onstage] encounters, I think, go so much deeper than someone’s email address. I mean, they certainly require that, and Bob gets to play with all kinds of people—and you’d have to ask Bob what he felt—but, for us, the man has loomed so large in mythology, in our arts, and in our music, that I still see Steal Your Face’s everywhere. I can close my eyes and still see the Dancing Bears dancing to “Cumberland Blues.” So it was just a real homecoming to get to play with him.

Have you ever had that kind of experience with any other sit ins?

You know, it was like meeting Pete Seeger backstage. In the case of Pete Seeger, the part that was the most like making music with Bob Weir was sitting with Pete while he talked. Story craft is just at the heart of Pete. He told this really long story that I just wanted to drink in. We’ve had such a special privilege in our lives as musicians to be able to be there with a lot of people who aren’t on this earth anymore. Plus making music with Cowboy Jack Clement, or Merle Haggard. These kinds of things are what the newspaper men of the future—God willing, if I live to be old enough—will be asking me. “What was it like to play music with Bob Weir? What did Merle Haggard whisper into your ear?”

Did he whisper something into your ear?

Yeah.

What was it?

I’ll tell you in 35 years. [Laughs.]

Before the festival, I was talking to the talent buyer for LOCKN’ for the LOCKN’ Times, and he was saying he’d been trying to get Old Crow on the lineup for years, but the timing never worked out. So I’m curious what your thoughts of the festival were after your first time.

I’m a Virginian, so I’m always going to want to play in the Old Dominion. But, as far as playing in Virginia goes, this was a really new experience, because I’ve never done a big festival here before, with music going on [that late]. What I’m used to with playing in Virginia is more like a rock festival or a bluegrass festival, or it’s a country thing or an Americana thing. But this was none of those, so it was exciting to be in the space of what felt like new, in the landscape of what felt so old.

You mentioned Old Crow not being too much in the jambands world, but I’ve heard that you’re a pretty big Phish fan. Can you talk about that connection and appreciation?

I haven’t seen Phish quite a few years. I kind of stopped going in my early twenties—that’s something I really did a lot of in high school, though. A lot of—I mean, there was a minute there when I’d seen Phish as much as I’d seen Bob Dylan. But Joe Andrews and Corey Younts in our band are still very much Phish concertgoers, along with all the variations of Phish. They’re really tuned in to what’s happening right now. I’m sort of tuned into Junta and Lawn Boy. But I’m really tuned into them. [Laughs.]

Any specific highlights from your Phish-going days that pop out in your memory?

One of my favorites was going to a show in Amherst, Mass., and not having a ticket and figuring we were just going to go hang out in the parking lot—being 16, having some mushrooms in my pocket and being so excited about just going to hang out in the parking lot. Stopping off on the turnpike on the way there, we go into the glass house [regional name for highway rest stops/service areas] and there was someone handing out Phish tickets to the show we were headed to. Those are the kind of miracles that occur in the lives in 16-year-olds on wild weekends in boarding school. [Laughs.]

I think, if we had our chops, Old Crow would be a jamband. But we were just never that virtuosic. We were a three-chord band that was really song-driven, and the best that we could do was with soul—not really the way we played, but the passion with which we played. But it’s all very self-taught and rudimentary chord structures. Our biggest influences are probably like the Memphis Jug Band and Workingman’s Dead. You can see, in the Dead, that there’s this pathway into the wilderness, from the sound of the Warlocks, or the music before that, the undergirding of the Dead.

Old Crow is really rooted in the folk revival, which I think is one of the most significant times in American music, when the first waves reappeared of a primal sound that had made American popular music so powerful. That wave was so strong that there were echoes of it resounding even 30 or 40 years later in the Shenandoah Valley, when Critter [Fuqua] and I, in the late 1980s, started playing folk music. It was that colossal. What really inspired us was to be true to it. The ideology of the band was still in its infancy and richly affixed to this concept of, “Gotta keep the old music strong, or else it’ll die.” And, you know, that’s the way a 20-year-old thinks. What I would tell that 20-year-old is just to rephrase it a little bit—you’ve gotta make the old time music strong so that you can give it away, again and again, so that it’ll be worth giving away and won’t make a memory, but rather something present and fun.

Do you ever have that fear anymore?

No, I think it’s in great shape. I think probably more harmonicas, banjos and fiddles have been sold in the past 15 years than at any other time. So yeah, I think we’re doing great, in terms of the cultural preservation of the music of the state of Virginia and other places. But, as the band is growing into the 21st year of its career, we have been able to change that loyalty considerably and stretch out into lots of new directions.

Having Bob up there affirmed the feeling and emotion in the band that we could actually play for a long time if we want. We could jam. And so, we started playing a couple of Phish tunes in our set—most of that is because we were playing in Vermont, and we always have the tendency to play [regionally appropriate covers]. When we play in Detroit, we sing “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”; in Seattle, we might do Nirvana’s [version of] “Molly’s Lips” or something like that. So, going up to Burlington, we’re likely to play some Phish. And our audiences down South aren’t as appreciative of us doing Phish…and we’ve learned that the hard way. [Laughs.] With the blessing of Bob—in all his Bob-ness—I feel like we could probably go forth and sew a new roots-music/jam row and grow some pretty unruly crops.

1 Comment comments associated with this post

Raising the Dead: Ketch Secor Talks Old Crow Medicine Show’s Live at The Ryman, Ken Burns’ ‘Country Music’ and Playing with Bob Weir – jambands.com | Prometheism Transhumanism Post Humanism

October 8, 2019 at 4:43 pm[…] Read the rest here: Raising the Dead: Ketch Secor Talks Old Crow Medicine Show's Live at The Ryman, Ken Burns' 'Country … […]