Anti-

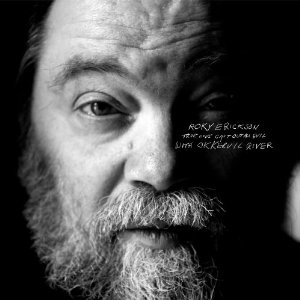

It would be easy to compare Roky Erickson to the late Syd Barrett, founder of Pink Floyd: both psychedelic music pioneers who spun out of the mainstream orbit early in life, having flung open some sonic doors before they left that could never be closed again.

There’s one big difference, though: Roky Erickson made it back.

Maybe a better comparison would be likening Erickson to Woody Guthrie. Rather than hopping freight trains and drinking tin-can coffee around a hobo campfire, Erickson took some long journeys into the uncharted territories of the mind, stumbled down into the deep, dark places of the soul, and in the end, was saved by the heart – battered but alive.

Before San Francisco became the epicenter of the 60s psych scene, Erickson and the 13th Floor Elevators were using their home state of Texas as mission control. Their 1966 debut The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators busted sound barriers, and still influences bands today. A steady diet of inner space travel took its own toll on the band, but it was the years spent in the Rusk Maximum Security Prison for the Criminally Insane that gutted out Roky Erickson’s spirit. (The crime: possession of one joint. The advice given to him by his court-appointed attorney: plead insanity.) Regular blasts of electro-shock therapy and daily doses of Thorazine were the standard back then.

The years following his release from Rusk were full of blackness lived out against a soundtrack of weird horror-rock songs written by Erickson. His marriage fell apart; he lost touch with his son; he ended up back home living with his mother. There was a period when he was convinced (and wanted legal documentation to verify that) he was “NOT a member of the human race and, in fact, from a planet other than earth.” By the late ’80s, the music in Erickson’s soul was drowned out by the voices in his head. At that point, he was holed up in a housing project, his small apartment filled with the roar of several televisions and radios playing at once to keep the voices at bay. His physical health was in rapid decline as well. Roky Erickson was a name for the “Whatever Happened To …” lists, forgotten by most of the world, but remaining an inspiration to those who remembered.

It was Erickson’s younger brother Sumner who began the process of turning Roky’s life around in 2001, coaxing him to come live with him in Pennsylvania. Roky’s now-30-year-old son Jegar reconnected with him. The right medications were prescribed; a life-threatening dental abscess was taken care of and Erickson was fitted with a new set of dentures (paid for by longtime fan and fellow musician Henry Rollins – one of those who remembered). Eventually he moved back home to Texas and got back together with his wife Dana. He bought a house and his first-ever car. And – maybe the key to it all – Roky Erickson had begun playing music again.

In 2008, the band Okkervil River was asked to back Erickson at the Austin Music Awards and the short set by “Rokkervil” floored those in attendance. It was obvious that Okkervil River knew how to tap into Erickson’s vibe and not only complemented him, but inspired him as well.

Which brings us to the newly-released True Love Cast Out All Evil, with Okkervil’s Will Sheff masterfully melding his band with Erickson in the studio. Throughout the album, producer Sheff’s respect and admiration for Erickson shines through; he knows when to add some sonic color, but he also knows when to give Roky room to be Roky.

One might expect that Erickson would emerge from his decades of darkness with a soul full of bitterness – but True Love Cast Out All Evil is just the opposite. What you have here is a very personal document that combines an almost childlike appreciation of life with an insight that could only come from having been there and back.

The album begins with a crackly lo-fi recording of Erickson made during one of his mother’s visits to Rusk. Here we have a very young-sounding Roky singing “Devotional Number One”:

Jesus met Moses

Drinking from a well

Moses had thought he was Jesus

Moses had just got back from Hell

Erickson does a very simple strum on an acoustic, backed by a fellow inmate on a second guitar. (The majority of Rusk’s population was in for acts of murder.) The rawness of it all – the sound, the setting, the circumstances – will numb you. Ever so gently, Sheff blends in a newly-recorded string section, resulting in a beautiful warmth that envelopes all … until it gives way to an old recording of Erickson’s jumble of cranked radios and televisions blaring a sonic force field. In a little over 2 brilliant minutes, Will Sheff manages to introduce us to Roky Erickson’s personal Hell and prepares us for the journey inward.

At times Erickson almost sounds like a weary, soulful John Prine, as on “Ain’t Blues Too Sad”, with its stark (yet gently-delivered) Rusk reference:

Electricity hammered me through my head

Until nothing at all

Is backwards instead

But he does not die

And no one dies again

And may he live

Blow the wind

At other times he snaps out a lyric like a young Steve Earle rocking it with the Dukes (“Bring Back The Past”). Again, Sheff and Okkervil River rise to the occasion on each cut, being what they need to be to provide the right foundation.

“Goodbye Sweet Dreams” documents some of the ache Erickson felt when he allowed himself to remember his losses, while “Be And Bring Me Home” shares some of the basic pleasures he regained. I love my family always, Roky tells us. Special and magical music – these are feelings from one to another.

The back-to-back placement of “Please, Judge” and “John Lawman” represent some of the darker moments on True Love Cast Out All Evil. The former is a plea for freedom for the innocent just before the cell is slammed shut; the latter a slamming, pounding ode to those who abuse their power. But the title track’s message of absolute faith pulls the mood clear of the wreckage of the past – and from there the album continues to climb out into the sun with “Forever”, “Think Of As One”, and “Birds’d Crashed”.

True Love Cast Out All Evil concludes with another reel-to-reel made inside the walls of Rusk Maximum Security Prison, “God Is Everywhere”. But this time, there is also the sound of free-to-be songbirds added to the mix. And when Sheff fades in some gentle strings to bring things to a close, it seems as if the music has risen above all the darkness and pain.

Just like Roky Erickson.

No Comments comments associated with this post