There are supergroups and then there’s Our Native Daughters.

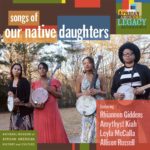

Featuring former Carolina Chocolate Drops Rhiannon Giddens and Leyla McCalla; Birds of Chicago’s Allison Russell; and Amethyst Kiah, this band of multi-instrumentalist black women tells the stories of America’s darkest open secret, its legacy and its impact on women of color on its exceptional debut, Songs of Our Native Daughters, which features one dozen originals and a cover of Bob Marley’s “Slave Driver.”

This is Giddens’ baby – she’s the only Daughter to appear on every track. But they are all key to the album’s impact, as they team to write and co-write tracks, add breathtaking vocal harmonies and contribute a dizzying array of instruments including Giddens’ percussion, fiddle and banjo; McCalla’s cello, guitar and banjo; Russell’s percussion, banjo and clarinet; and Kiah’s guitar, banjo and percussion.

They’re backed by a few choice session players – including Giddens’ longtime associate and producer Dirk Powell – on guitar, mandolin, fiddle, accordion, bass and drums.

Kiah’s “Black Myself” opens the LP and serves as the Daughters’ mission statement. It’s a bluesy rocker in the vein of Led Zeppelin’s “When the Levee Breaks” and speaks to the alienation black people continue to feel and the strength with which they persevere. Buffeted with accordion and electric guitar, this track is an outlyer in the album’s overall atmosphere, but is key to establishing the story about to unfold.

“Ah, you steal our children, but we’re dancing/ah, you make us hate our very skin, but we’re dancing,” Giddens sings on the sparking “Moon Meets the Sun,” where the album moves from contemporary to antebellum America with just one fade.

Russell sings of her Ghanaian relative, a slave, on “Quasheba, Quasheba,” and recalls a life that saw her forebear “raped and beaten/every baby taken/starved and sold and sold again.”

And then Russell rejoices in Quasheba’s legacy.

“By the grace of your strength we are home,” she sings.

Songs of Our Native Daughters is an album that puts banjo music back in its proper context. Though mostly associated with rural, white folks today – “I pick the banjo up and they stare at me, ‘cause I’m black myself,” Kiah sings on the opener – it comes from Africa. And like so much, it was co-opted and its history forgotten.

The Daughters sing of other systematic lies on “Blood and Bones,” a deceptively uptempo number whose music belies its message – that there were no winners in an institution where one race claimed inherent superiority, but knew instinctively their way of life was wrong on every level.

“When they bound us to their will/they trapped themselves in hell as well,” Kiah sings.

“Slave Driver” retains Marley’s reggae melody but outfits it in bluegrass instrumentation and crystalline harmonies. “Better Git Yer Learnin’” is rendered as a front-porch children’s tale with banjo, fiddle and shakers. John Brown’s better half finally gets her due on “Polly Ann’s Hammer,” a song Giddens challenged Russell and Kiah to write. And hard-earned redemption finally arrives on the album-closing twofer of “Music and Joy” and “You’re Not Alone.”

But the most powerful moment is the most musically stark. “Mama’s Cryin’ Long” features four voices singing call-and-response over handclaps and drums and needs just two minutes to tell a complete tale of enslavement, rape, black reprisal and white revenge.

“Mama’s dress is red,” Giddens sings.

“It was white before,”her sisters answer one of the most chilling pieces ever put on tape.

No Comments comments associated with this post