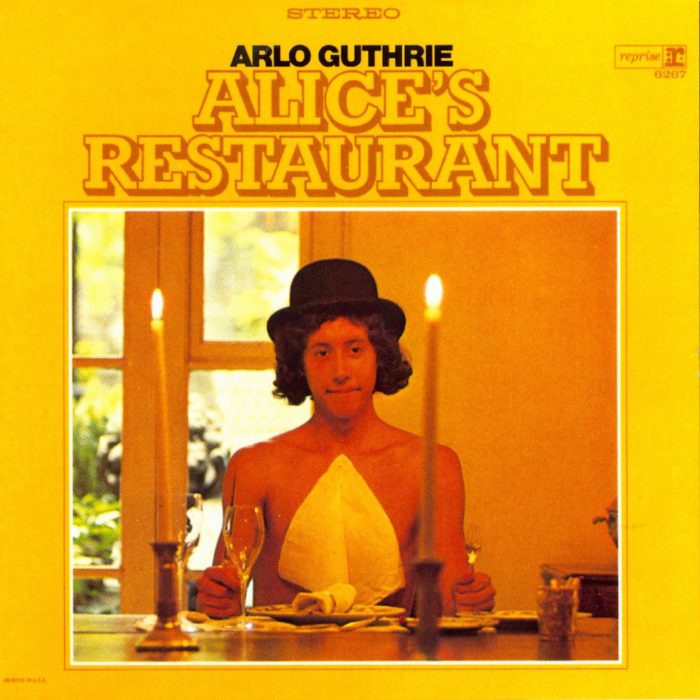

Since he released his classic story song “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree” in 1967, Arlo Guthrie been considered by some to be a Thanksgiving mainstay on par with turkey and pumpkin pie.

That almost 20-mintue autobiographical tale—which set the hypocrisy-ridden realities of the draft against the backdrop of Thanksgiving 1965—has not only aged into one of the most enduring Vietnam-era protest songs anthems, but also blossomed a storied holiday tradition in its own right.

The son of Woody Guthrie of Martha Graham dancer Marjorie Greenblatt (and grandson of acclaimed Yiddish poet Aliza Greenblatt), the 72-year-old singer-guitarist grew up in the folk world and has stayed true to that storied tradition’s traveling minstrel approach throughout his 50-plus year career. (Arlo has described folk music as “the original social media.”) In addition to his own revered works, many of which—including “The Alice’s Restaurant Massacree”—were workshopped live, he’s helped keep his father’s work relevant, recently celebrating the elder Guthrie’s centennial with a retrospective tour focused on his extensive catalog.

For over five decades, Arlo has also nurtured a deep connection with one of his family’s closest friends, Pete Seeger. This past summer, he honored Seeger with a special concert in Albany, N.Y., just north of his longtime Hudson Valley home. And while the always wry Gutrhie quips, “I don’t remember what I did there, but, I just showed up to celebrate Pete’s contribution with others who were also inspired by him,” he has lovingly carried his mentor’s work into the modern Americana era.

For many years, Arlo and Seeger

marked Thanksgiving weekend with a special concert at New York’s Carnegie Hall,

a tradition that always felt well timed with “Alice’s Restaurant.” Seeger

passed away in 2014, but Guthrie has kept the tradition alive since then,

weaving in members of his family like his daughter Sarah Lee, son and bandmate

Abe and, last year, The Band associates The Weight Band.

This year, after a half century of annual gatherings, Arlo has decided to

retire the Carnegie Hall series, in order to focus on touring more intimate

markets, hosting events at the converted church where the actual “The Alice’s

Restaurant Massacree” story took place and working on his “rock farm.”

“You just wait until spring and pick up more rocks,” he says with a laugh of the later project.

Shortly before his final Thanksgiving at Carnegie Hall, Arlo discussed his lifelong friendship with Seeger, his unconventional bar mitzvah and why he’ll finally be able to enjoy leftovers next November.

Pete Seeger was a huge part of your

Carnegie Hall shows for many years. He was also very close with your father.

What role did he play in your development as a young musician? Do you remember

the first time you met?

I first met Pete and his wife, Toshi, when I was a little kid. We’d go up to

their home in Beacon, NY just to visit. It wasn’t like I was personally

visiting them, it was really my mom and us kids just going along. We were told

to “go play outside,” while they had a chance to visit. As I grew up, I’d see

Pete in the office of Harold Leventhal, who was my father’s manager. He was

Pete’s manager as well, and he eventually became mine. So, I was familiar with

Pete and had attended many of his shows. We found ourselves together at the

many demonstrations and protests taking place during the late-1960s.

Eventually, it bloomed into a collaboration that lasted over 40 years. I loved

working with him—no set list, no preparation, no rehearsals. We’d just step out on stage and play it by

ear.

We played together [at Carnegie Hall around Thanksgiving for years]. I did my

first show at Carnegie Hall back in November of 1967, but it wasn’t tied to the

holidays. It was a coincidence. In fact, until the early 1980s our shows at

Carnegie Hall were scattered throughout the year. It started to be a tradition

in the early 1980s when Pete and I returned year after year on the same days

following the Thanksgiving holiday.

Pete never really became ill—he just

became quite old which made his public efforts more difficult. He called me in

his 80s suggesting that he’d be doing less and less big shows. He said, “Arlo,

I can’t sing like I used to sing. I can’t play like I used to play.” I said,

“Pete! Look at our audience—they can’t hear like they used to hear. It might

not be a problem.” He laughed and said, “Well, maybe you’re right.” And we

continued to perform together for many years.

This

year’s performance is being billed as “the last annual” Thanksgiving Carnegie

Hall show. What made you retire the series and is it something you plan to

revive for “bigger anniversaries” tied to the Alice’s Restaurant LP in the future?

There are a lot of reasons to exit the annual shows. The audience I inherited

from Pete, as well as my own, is getting older—many have already left. And

while most people of my generation would at least be familiar with my name,

most people under 50 have no idea who I am. I was never a Top-40 artist,

although we’ve broken into it accidentally a couple of times, so there isn’t

the excitement surrounding my concerts that there would have been decades ago.

The size and prestige of the venue isn’t warranted nowadays. There’s plenty of venues

around the country and the world that are more suitable, and I’ll be coming to

those places as usual.

[Next year], we’ll probably do what we always do with the notable exception of not having to go to New York City after Thanksgiving. For the first time in over 50 years we’ll get to munch on leftovers.

Donald Trump’s father, Fred, was your

father’s landlord for a time and he even wrote the very first well known

anti-Trump song, “I Ain’t Got No Home – The Ballad of Old Man Trump.” Do you

have any vivid memories of your families interaction with the Trump family at

that time?

Fred Trump was indeed our landlord. My dad didn’t like the idea of terrestrial

lords in general, especially landlords. More importantly, he didn’t like the

idea of forced segregation by landlords. I have no memory however of those

years as I was about 4 or 5 years old.

You have famously only performed your

signature song, “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree” on special occasions, but it

seems you have pulled it out more in recent years. Do you feel the song has

taken on new importance in our current political climate?

I’ve put it on the setlist for the occasional 10-year anniversaries. Beginning

in 2015, we celebrated the 50th anniversary of the actual events

that were the basis for the album, which came out in 1967. The movie came out

in November of 1969. So, it’s been on the setlist for a few years now. That’ll

conclude next year, in May of 2020.

This year marks the anniversary of the Alice’s Restaurant film, which was a

precursor to the era of music videos. Do you have any funny memories of trying

to “play yourself” in front of the camera?

Generally, it was an awful experience, because the song was based on real

events, and took 20 minutes to tell. Being a full-length feature film they had

to add 70 minutes of fiction to meet the running standards of the times. So I

was less than a third real, and more than two thirds fiction in the movie. The

same was true for everyone whose real names were used in the film.

Your

music has long been associated with Thanksgiving and the holiday season in

general. Your family is also a blend of religions. Are there certain elements

of the traditional wintertime holidays your family has embraced—from caroling

to lighting the menorah—over the years?

Our family loves getting together for the holidays. We celebrate in our own

ways, but generally have a private Thanksgiving dinner at the house the day

before the actual holiday. Then, we’ll go over to the church [The Guthrie

Center] and help out with our annual free Thanksgiving dinner. [Guthrie also

performed a special show at the church on Nov. 23.]

Your bar mitzvah has been historically

described as a hootenanny that blended tradition and modern music in a way that

feels inline with your career. What is your most vivid memory from that early

milestone?

The only thing I remember is the wonderful feeling I had when my father

arrived. All the attention in the room left me and focused on him. I was

relieved because the pressure was finally off.

You recently performed at the site of

the original Woodstock on the anniversary of the festival and covered Bob

Dylan’s “The Times They Are a-Changin’.” Can you talk about that song choice

and the anniversary celebration?

The owners of Bethel Woods promised to build me a stage for a free concert on

the original site. They did not follow through and there was nothing at the

original site—no sound system or other promised infrastructure. It was quite

disappointing. I took a guitar and stood where the stage had been built 50

years earlier, and sang Dylan’s “The Times They Are a-Changin’,” as it was

something I could sing with an acoustic guitar and no microphone. Later, we did

a show [held on the anniversary of the original Woodstock festival and timed

with a screening of the classic Woodstock

film].

You

recently expanded your backing band, including members of your old friends

Shenandoah. What brought them back into the fold?

We’re doing the last show of the tour with that band tonight [Nov. 22, 2019].

Beginning in February 2020 we’ll have a new tour, completely different in some

ways, with some songs carrying through from the Alice’s Restaurant tour, “Alice” for one. The band will be smaller

with just my son Abe Guthrie [keyboards and vocals], Terry A La Berry [drums

and vocals] and me. We’ll be joined by my daughter, Cathy Guthrie and her

singing partner, Amy Nelson, Willie’s daughter. Together, they are known as

Folk Uke. That tour will run until May 2020.

You

have spent the past few years actively paying tribute to your father’s music.

He had so many songs that touched on so many different sonic styles. Are there

certain songs or periods of his songbook that you hoped to bring to life at

this point in time?

I’ve actually spent my life furthering my fathers philosophies through his

songs and stories. He was an incredibly motivated writer on almost every

subject one can imagine. So when it seems appropriate I’ve included his work in

my shows.

1 Comment comments associated with this post

Patrick

November 30, 2019 at 10:57 am“has stayed true to that storied tradition’s traveling minstrel approach”

I would assume that Arlo doesn’t want to be associated with the traveling minstrel approach. Minstrel shows specifically depicted African Americans as caricatures of stupidity by white people dressed up in blackface.

Maybe there is a different way he honored traveling folk shows or maybe this is exactly what the traveling folkie was rooted in.