Before the tragedy of all tragedies befell The Allman Brothers Band- the accidental death of its founding leader and all-time great guitarist Duane Allman—1971 was a momentous breakthrough year for the band. After forming in 1969, and playing hundreds of shows from coast to coast, the Brothers had developed an improvisational alchemy peerless in rock music. The group recorded what would become the standard bearer of live albums, At Fillmore East, in March, displaying the ensemble at the peak of its prowess. In June, the Brothers had headlined the final concert ever at the Fillmore East, and by the end of July had seen the release of the Fillmore record to widespread critical acclaim.

In New York City for a promotional radio appearance, The Allman Brothers Band performed an hour-long set at A&R studios on the 26th of August, just two weeks after the murder in Manhattan of saxophonist King Curtis, (a friend of Allman’s for whom the guitarist recorded some sessions). The nine-song program was inspired work, showcasing the conflagration of six musicians focused as one, smoking through covers of “Statesboro Blues” and “One Way Out” as if they were the band’s own. Soon, the Fillmore East album would standardize much of the live repertoire, but the moment cuts like “Don’t Keep Me Wonderin’” and “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” were hitting the airwaves, it was revolution. The interplay between Allman and Dickey Betts was a renewing horizon of discovery, with the hellhound character of brother Gregg Allman’s voice coming into form, and the rhythm section of Berry Oakley and drum duo Butch Trucks and Jaimoe driving the freight train right through the Hi-Fi. Even at such heights of musicianship, the potential for even higher ground was more than possible; it was frighteningly, daringly probable.

Fate, and hindsight, can be cruel. Near the end of the show, Duane takes a moment to say a few words about Curtis and his passing. He mentions the King’s classic “Soul Serenade” performed at the funeral, then inserts the honey-sweet instrumental into the subsequent jam of “You Don’t Love Me.” It’s eerie to hear Allman speak of death and a musical legacy left behind, as he, himself, would die in a motorcycle crash just two months later.

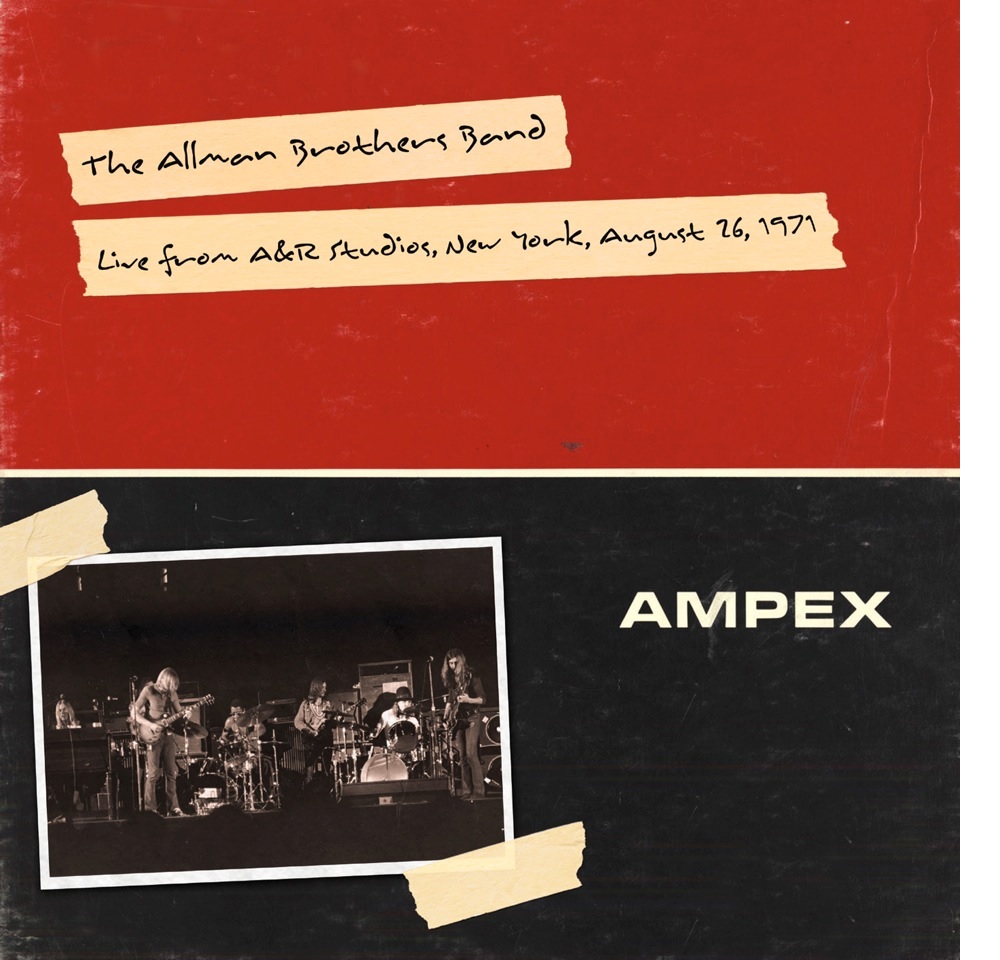

The A&R show, presumably taped in droves by home stereos, was widely bootlegged, and in the following decades considered quite a treasure of both performance and historical context. To have it officially released, cleaned up and remastered to a high polish from the original broadcast tapes, is to put it finally in the proper place for all to hear; the magnificence of The Allman Brothers Band in one of its finest hours of its finest year of 1971.

No Comments comments associated with this post