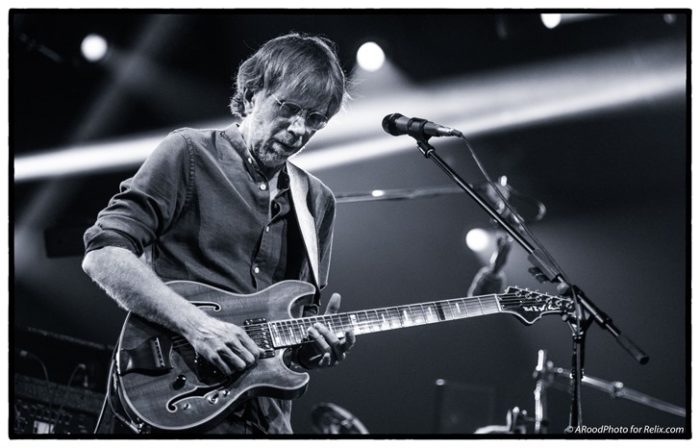

In an expansive new feature from GQ, a wide range of musicians go in depth on their experiences with sobriety, starting with their various issues with alcohol and drug abuse, through getting and staying clean (several times, in some cases) and continuing to create music. In all, the multi-artist interview covers the stories of Phish frontman Trey Anastasio, Jason Isbell, Julien Baker, Ben Harper, Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler, the Eagles’ Joe Walsh, DIIV’s Zachary Cole Smith and French singer-songwriter Soko.

The musicians, who range in age from early twenties (Baker) to early seventies (Tyler, Walsh), share an equally wide range of alcohol, drug and sobriety experiences, starting with their current states. “I have 25 years of sobriety,” Walsh begins, before adding, “But the important thing is, I haven’t had a drink today.”

Each of the subjects also share their initial forays into their vices of choice, with Anastasio recalling his first experience with OxyContin in 2000:

I remember it like it was yesterday. I was at a club—I was about to go onstage. As I often did at that time, I did a shot of tequila, and then I did another shot of tequila, because I really liked tequila. And then somebody said, “Do you want to try this?” and I said, “Sure, bring it on.” I had never heard of that drug in 2000. This guy had a pill, and he crushed it up and gave me a little bit in the form of a line. And I did it, and I remember thinking afterwards, “All my problems just went away.” I didn’t feel high or anything, it was just “Eureka!” And I went down the rabbit hole. By 2004 my band was gone. I couldn’t get off these things. It was horrible. So when I was arrested, December 15, 2006, my car was full of various opiate substances—oxycodone, Percocets, heroin.

One of the most compelling aspects of the interviews is the different reasons that the musicians give for both getting into and getting away from drugs and alcohol. Tyler enthusiastically remembers the days of playing huge venues then going “clubbing with Jimmy Page” all night. “After two encores in Madison Square Garden, you don’t go and play shuffleboard. Or Yahtzee, you know?” he says. “You go and rock the fuck out. You’ve done something that you never thought you could, and you actually think that you are a super-being.”

On the other hand, the younger Baker remembers the pain of being “very scared and uncomfortable and sad” and using drugs as “a numbing agent, or an escape mechanism.” Isbell sums his experience up by saying, “For every hour of fun, I had a week of misery that I put on myself,” while Anastasio follows up by noting that those days were “tons of fun. Mountains of fun. Nothing but fun. But then it wasn’t fun.”

Getting into their eventual decision to get sober—whether it was recently or decades ago—the musicians speak of issues with friends and family, and Anastasio talks about losing his band and struggling with staying sober:

I had been trying to stop, oh man, for years. I had checked myself into a rapid detox hospital—it didn’t work. And I would go home and clean myself up. It was the kind of thing where every time I went back out on the road, it would just fire back up again. I would do yoga [laughs], go the gym, and all this stuff that I thought would address the problem. And I would start a tour, and by set break of the first show, there would be 30 people in my band room and it would all come back.

When I got arrested, I was very sick and I was in the process of losing everything that was dear to me. I had not played a show for two years and was out of communication with the guys in Phish. I was very sick and skinny and crazy and mean. It hurts my head to talk about this stuff, but it’s true.

It all seemed to happen so fast. I had done work a few years back with the Vermont Youth Orchestra, which was something I was so proud of. And when I got arrested, my mug shot was on the cover of this local paper for something like six days in a row. All I could think about was all of these parents and all of these kids having to look at this, and it just filled me with so much shame. I just couldn’t figure out what had happened. Like: What happened?

The interviews also get into the fears each of the musicians had about getting sober—frequently the answer to that question is losing their creativity or sense of humor, though Anastasio notes that he felt he’d lost his humor because of the drugs, along with recalling how “90 percent” of the people he associated with went away, leaving behind the real friends and family that cared for him.

Anastasio and the others also speak on their current life and artistic work, how those have changed and grown, and though many of them recognize the quieter quality of their existence as compared to previous eras of their life, they all appreciate their separate sobrieties and look to the future with hope. Anastasio discusses a times when he questioned whether his “mojo” would return:

When I first got sober, someone said, “Is this going to be hard for you to go back, without the rock ’n’ roll excess?” And I said, “No, because for the first 15 years, there was none of that.” We played chess a lot, and Tetris.

There was a period of adjustment. There was a time, three or four years in, where I thought I had lost my mojo. I had lived my life with reckless abandon to great effect—just pushing every boundary that was in front of me. If there was a fence, I’m gonna step over it. And then to be in this thing where if you jump over the fence, you wake up in a blue suit. In a cell. It kind of turned me into a cautious person. I was really nervous and scared about everything for a while. I would drive the car at 49 miles an hour, with nothing in the car, and still think I was going to get pulled over and yanked out of my life by some authority figure. Sober people around me kept reminding me “More will be revealed” and “Just keep going,” “Don’t quit till the miracle happens,” and all those sayings they have. And lo and behold, they were right. I thought my mojo was gone, but you find a new kind of mojo.

The important thing is to know that there is a way out. And the life at the other end of that is a beautiful life. Everything bad turns into an incredible gift. If people can find the way out. But I sympathize with how hard it is and how hopeless it seems.

Read the full GQ piece here.

2 Comments comments associated with this post

Mark

January 15, 2019 at 12:38 pmVery inspiring, thanks for including this.

45 days clean here, never felt better!

Tbot

January 15, 2019 at 9:24 pmA great read …. I will have 1 year sober next week and it is moving to read articles like this.