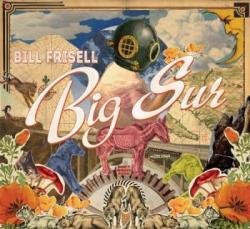

As big, bold, quirky, and lovely as its namesake (and birthplace) Bill Frisell’s new Big Sur album is destined to be a classic in the guitarist’s catalog. Frisell has made a career out of defying musical boundaries and shrugging off genre labels; you’ll most likely find his albums under “jazz,” but know that this man can play the blues, pick the grass, twang the boards off the side of the barn, and jam with the trippiest of them.

Frisell’s Big Sur – featuring his new “Big Sur Quartet”: violinist Jenny Sheinman; cellist Hank Roberts; Eyvind Kang on viola; and drummer Rudy Royston – is the result of a commission by the Monterey Jazz Festival, which landed Frisell a residency at the 860-acre Glen Deven Ranch in Big Sur, CA. Just the man, a guitar, and his notebooks – in a setting that offered beauty, solitude, and inspiration.

We talked with Bill about the experience of having complete freedom to be and to create – with the occasional wild animal thrown into the mix.

BR: Bill, when I first heard about this project – before I actually heard the album – I thought you might be doing another project like the one based on Hunter Thompson’s “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent And Depraved” article.

BF: Oh, yeah … (laughs)

Which concerned me, because as beautiful as Kerouac’s Big Sur is, there’s some serious darkness there …

Oh, I know – I was actually reading it while I was up at Big Sur. It was incredible. Kerouac’s description of his arrival at Big Sur at the beginning of the book was sort of an exaggeration of my own. He was going up there to clean himself up from drinking or whatever; I was going to clean up my brain from … you know … all the chaos around me.

But he describes getting there late at night – he was walking from Monterey or wherever he was coming from – and describes this ravine and he runs into a donkey and all this stuff happens. When I went there, it was in the night – the flight was cancelled and I was really late – and I’m driving up this narrow, dark road and I don’t know where I’m going.

It was kind of amazing: he just nailed the description. Also, there’s this sort of darker thing about it, too; it’s spectacularly beautiful and spacious … but there’s this underbelly to it, at the same time.

Of all the songs on the album, if I was going to pick one that could be a soundtrack to the Kerouac book, I guess it would be the title track. It seems to capture some of that tension and darkness … and the beauty.

That’s cool. Once I got there and started writing the music, things kind of … (laughs) … I just sort of entered into the music. But being there gave me the space in my head to just write. I wasn’t trying to really capture some picture or anything – I was just sort of … writing music.

The very last thing I always do are the titles; I go back and listen to the stuff and say, “Well, this must remind me of something …” (laughter) It’s always like that – the title is sort of an afterthought.

That’s interesting. How much of the music do you think was generated by being at Big Sur, rather than just a result of being isolated like that?

There was this double thing of incredible space and beauty around me, which – of course – affected me, as you say. But even more important was the space in my own mind to just be with myself. That is so rare these days; I didn’t know what time it was; there was no internet; no phone; no TV – none of that stuff. It was just basic follow-through of whatever. There was no pressure at all.

And even though I was writing the music for the Monterey Jazz Festival – that’s where we played the music – it was so far into the future that I didn’t feel that deadline thing either.

You had a completely empty canvas to work with.

Exactly. I’ve never had an experience quite like that.

Had the Monterey Jazz Festival done anything like that previously? I know they’d commissioned pieces, certainly, but had they set someone up in an environment like that to write?

I think I might’ve been the guinea pig for that. (laughter) I think they’d been talking about doing it for a while. There’s one song on the album called “Song for Lana Weeks” and she’s the woman who works for the Big Sur Land Trust. Lana and Tim Jackson, who’s the Monterey Jazz Festival’s Artistic Director, have been thinking about this for quite a while.

Some people wouldn’t want to go up there and be all by themselves, you know? So they had to find somebody. Tim knew me – and knew me well enough to know that I might be interested … and I definitely was.

Would you go back?

Yeah … for sure! It was like paradise for me.

So, no cellphone; no laptop; no TV. The big question is, what did you take for instruments?

The first time I went – I went twice – was in April of last year for 10 days. And I just had a Collings guitar with me.

I always have just one instrument with me at a time. Someday – when I grow up (laughter) – I’ll have roadies and all that stuff. But whatever I can carry with me is what I have.

So, a Collings acoustic?

No, actually it’s a semi-hollowbody electric that’s kind of like a 335 Gibson. I think they call it an I-35.

Oh, sure – I have a Collings mandolin, which is a much better instrument than I’ll ever be a player. It’s beautiful.

Oh, they’re just incredible, aren’t they? I have a Collings dreadnought, too – it’s an amazing instrument.

So you arrived at Big Sur during the night and took in your surroundings the next morning. How long was it before the music showed up; before you started to write?

Well … I think right away. It’s hard to say. I’d just walk around and all day I’d be writing something. It’s almost like drawing or … or …

Sketching?

Exactly. So I’d walk – even without my guitar – out on these trails with a little notebook and try to write down melodies. There were tons of stuff; what ended up on the record or what we did for the gig is just a small part of it. I should go through those notebooks more to see what else is in there.

No Comments comments associated with this post