Part III – Colours of the Hidden Palette

…far from home, I often feel homesick for the land of pictures.

– The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh, selected and edited by Ronald de Leeuw

RR: “Suite: Liberté,” another track that was put together in an interesting fashion, actually contains two parts, “Megumi” and “Huria Watu.”

PF: Oh, right—the instrumental, yes. When I first got the Hank Strat—I have one of those little digital two-track recorders, and I turned it on in my studio—that intro that you hear is me playing that Strat with the Hank Marvin echo going through a Fender Tweed Deluxe [amp]. It’s just such a sweet sound that it inspired me to play that little piece, which is on-the-spot. That was being written as you hear it. From that—I thought that was just a demo of the thing—I decided to write a tune that went with it, and that would be just the intro. That was the second piece [“Huria Watu”], so I could have something with more of a bluesy feel for another instrumental, and I decided to link them all together, so we could have almost three pieces in one, but it’s actually two complete pieces hooked together.

I had continued the thought from “Asleep at the Wheel” [the track that precedes “Suite: Liberté” on the album], which is about children that are born into not as good as circumstances as we are, but it also goes into child kidnapping. This was all inspired by the Japanese girl, Megumi Yokota, who was kidnapped by the North Koreans from Japan. They were doing this quite frequently about 30 years ago. Some of them have been returned; she’s never been returned. The rumor is that she has been working with Kim Jong-il’s as first, the children’s nanny, and now, his assistant. I watched a program on Independent Lens on PBS. It was her parents, who are still dealing with the Japanese government, who are dealing with the North Korean government, who are just stonewalling them about it. I continued that because I thought the melody of what would become “Megumi” was so poignant that I dedicated that to her and her family.

The second part, the blues part is “Huria Watu,” which means “free, independent person.” It’s all about personal freedom for everybody. Really that’s what it’s all about. A little deeper. (laughs)

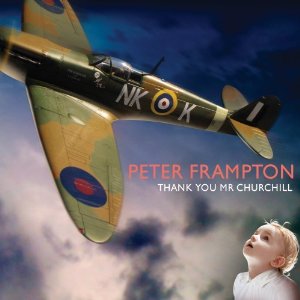

RR: The musical and lyrical themes seem to flow and connect with each other quite well on Thank You Mr. Churchill because then we have another song about current events, which is equally relevant with its Wall Street references, “Restraint.”

PF: Yeah. Yeah. I think what it was was that I came up with what seemed to be a very ominous couple of riffs that I put together. That lent itself to the ominous lyrics (laughs) being about these greedy pigs.

RR: And they have the opposite problem, as compared with Megumi, of having too much personal freedom.

PF: Exactly. (laughs) It was a pretty easy song to write once I got the lyrical content. I did bring Gordon in because I realized it was going to be a really powerful song, one of my favorites, and one of the latter songs that I wrote for the album, and I felt it was definitely on a different and more original direction than even some of the others. So, on the second verse and choruses, I brought Gordon in on the lyrics to help me. The first verse is definitely all me, and then, as it developed, I needed some help there because I wanted it to be right, to be as good as possible, so Gordon came in, and helped me finish that one.

Part IV – The Man and the Music

In the strong autumnal winds he rushed along ignoring the new dark knowledge he now half-understood—that to triumph was also to wreck havoc.

– The Town and the City, Jack Kerouac

RR: A really fine rocker, as well. I wanted to ask you about a song with another memorable hook, “I Want it Back.” What is the story behind the lyrics?

PF: It’s basically about when you make a wrong decision by not taking care of a relationship, and when it’s gone, you realize that was the one for you, and you want it back. There’s a little humor in the lyrics there: “sometimes I don’t listen when you talk, but when I look at you, baby…”—it’s that kind of thing (laughter), which we’re all guilty of. [Takes a harsh tone] “You’re not listening to me!” (laughter)

That one came from a riff I did as an intro to our last number [of the set], last year, “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” I started doing this riff over the last 18 months, that opening riff, and when I would do it, and then pause, the audience would go: “YEAH!” It built up and up until I decided I had to make a song for that one, so it turned into a song.

RR: Staying with the catchy riff theme here, how about “I’m Due a You?”

PF: That was one of the very first tracks that I did in my studio, just me with a nice, clean Tele-y sound, thinking sort of Motownesque, that sort of feel to it. [Author’s Note: Frampton used a 1987 Fender “J.W. Black” Custom Shop Telecaster on the track, as well as two different Gibson Les Pauls—an LP Standard, and a Peter Frampton LP Custom.] It’s, again, tongue in cheek—we go through all of these terrible things, and then, basically, I’m due a you. At the end of the day, I know what would really be good, I’m due a you. I’m definitely due this very nice lady.

RR: Many textures, themes, colors, and influences are explored on the album, and you hit upon a recurring theme throughout—your roots. Let’s discuss the family ties to “Vaudeville Nanna and the Banjolele.”

PF: Right. Right. Right. Yeah, that one came from a loop that I found, and presented that to Gordon. We sat down one day, and came up with that. That morning, we had been talking about what made me start playing guitar. How did I start? What got me into all of this? It just sort of spiraled out of control. Each verse was about Mom and Dad, and then about the family. It really is the story of how I started in music, and it’s that banjolele.

RR: Yes, the song addresses your origins in music, but afterwards, in the midst of your career, and long afterwards, there was a dichotomy between your overall image and the importance of your work as an influential musician. I am sure you have thought about this from time to time in some way, but did you perceive this dichotomy between your image and your role as a musician?

PF: Absolutely, which has been very frustrating, but not anymore. I think, as I was talking to you about in the very beginning of the interview, I just feel that now that the pressure’s off and everything, which has been for a while, obviously, many years, being the musician that I am, and always have been, I’m now being accepted on that level, and it couldn’t be better for me. I do feel that my peers have always known, but to be accepted on that level, finally…

I think the audience is turning around. I still get people who say, “Grow your hair back. Where’s your golden locks?” But, those aren’t really the fans that I want anymore, or ever really did want as the musician. It was basically the fact that my parents are good-looking. (laughter) And I’m not going to blame them. It doesn’t matter what art form you’re in—whether it be music, acting, or a model, or whatever, but acting and a musician, mainly—if you’re too good-looking, people think that you’re not talented.

Laurence Olivier said this about Vivien Leigh, who was his wife for many years: she was an amazing, amazing actress, but because of how beautiful she was, a beautiful woman, people tended not to take her as seriously as good as she was. When I heard him say that, I translated that to myself. Maybe that was the perception that becomes that—if you’re all of sudden accepted for being a good-looking person, people think that you can’t be talented. You only got where you got because of the way you look, which is not true, but that is the perception. You can’t change it. It’s very hard to change.

No Comments comments associated with this post