Simon & Schuster

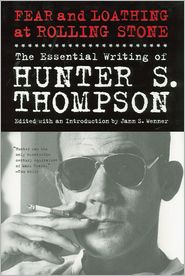

As the seventh anniversary of the untimely suicide of gonzo journalist and pop culture icon Hunter S. Thompson approaches, his name has faded from day-to-day discussions of great American writing. The publication of Fear and Loathing at Rolling Stone serves as a powerful reminder of just what the American literary community lost when Thompson took his life, and how influential his unique satirical insight into modern society remains.

Blurring the lines between fiction and reality, with openly admitted heavy drug and alcohol use obscuring the “realness” of his adventures and observations even further, Thompson was nonetheless one of the truest chroniclers of current events this country has ever produced. Thompson mostly worked as a freelance magazine journalist, with his books coming from collections of articles, and from 1970 through 2004, much of his best work was published in Rolling Stone.

Fear and Loathing covers Thompson’s career at Rolling Stone more or less chronologically, starting with his first piece for the magazine, “The Battle of Aspen: Freak Power in the Rockies,” published in October 1970. Right off the bat, Rolling Stone readers were treated to Thompson’s mixture of manic exaggerations and caricatures with surprisingly level-headed and analytical commentary on politics and society. Thompson astutely observes that one of the problems he encountered on his nearly successful run for sheriff of Aspen, CO on a “Freak Power” ticket was that the typical “freak” had chosen to completely drop out of mainstream society, rather than try to work for change from within.

Other highlights of Thompson’s early Rolling Stone output collected here are articles that were part of two of his most successful books: “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” and “Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72.” Even readers already familiar with these works will find something new reading individual excerpts the way they were originally presented. For example, a campaign trail entry from January 1972 opens with a decidedly non-Gonzo paragraph describing the still-lush lawn of the Washington, D.C. condo he had rented that evokes Hemingway in how perfectly it describes Thompson’s surroundings with a minimum of words. It is easy to forget that underneath the crazed, drug-fueled misadventures and wild man persona, Hunter Thompson was an incredibly talented writer who took his work very seriously.

Readers familiar with Thompson’s career path know that as time went on, the pressures of fame and continued heavy substance abuse took their toll on his writing, and his submissions to Rolling Stone became less frequent and generally less impressive as the 70s rolled into the 80s and then the 90s and 00s. He was still capable of brilliant insight until the end, though, and the highlight of his post-early-1980s Rolling Stone career is probably the legendary article “Fear and Loathing in Elko,” a totally fictitious tale about a violent, drunken evening spent with Judge Clarence Thomas originally published in January 1992. The highly detailed description of the encounter with Thomas, including hookers, guns, pornography and extremely heavy drinking, is probably the last example of Thompson writing A-list Gonzo material.

Throughout the more than 30 years of journalism this book covers, one constant thread that permeates all of Thompson’s writing is a pronounced sense of moral outrage. Thompson was forgiving of (and indulged in) all manner of immoral behaviors and vices, but clearly had no stomach for greed, corruption or misuse of power. He was exposing the shady alliance between big business and politicians before the parents of some of today’s Occupy Wall Streeters were born.

While Thompson reserved his harshest political criticisms for Republicans (especially his archnemesis Richard Nixon), he did not let Democrats off the hook when he saw them falling short. In particular, he called 1968 Democratic presidential candidate Hubert Humphrey a “living, babbling insult to the presumed intelligence of the electorate,” and after abandoning his participation in a group interview with Bill Clinton in July 1992, he revealed that Clinton “has no Sense of Humor.” Tellingly, the only politicians Thompson shows pure affection for are Jimmy Carter and George McGovern, two men generally seen as too honest and decent to have succeeded in Washington.

The book also includes a number of notes and memos exchanged between Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner and Thompson during the years, providing a fascinating look at how much effort and planning went into what were seemingly carefree rants tossed off at a moment’s notice. The two constant factors in all the Wenner-Thompson correspondence are Wenner’s exasperation at Thompson’s habitual lateness for deadlines and Thompson’s need for payment, preferably in advance (nobody who has worked on either side of the freelance writing fence will be surprised by this). The correspondence also hints that as good as Thompson’s body of work with Rolling Stone was, it could have been even better, as innumerable ideas for what sound like brilliant articles are raised but never come to fruition for one reason or another.

Fear and Loathing at Rolling Stone is a valuable collection of writing that changed the face of modern journalism. Thompson fans will have a pleasant reminder of why they love his work so much, while new Thompson readers can get an overview of why exactly this hell-raising drunken reprobate is so damn popular. I received this book as a birthday present; it would undoubtedly be welcomed by many as a present for Christmas or Hanukkah, as well.

No Comments comments associated with this post