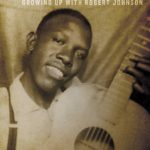

While it’s never wise to judge a book by its cover, the cover of Brother Robert: Growing up with Robert Johnson is utterly remarkable.

It’s a never-before-published picture of the legendary bluesman, posing in a Memphis photo booth and smiling with his guitar in hand.

It comes courtesy of Johnson’s stepsister, 94-year-old Annye (pronounced On-yay) C. Anderson, who wrote the book with Preston Lauterbach.

That brings the number of known photographs of Johnson to three.

The cover, as Lauterbach writes inside, is the book’s biggest selling point. But he and Anderson provide invaluable context to a life that has precious little.

For those who have listened to Johnson’s scant recordings, “it is easy to feel we have spent time with (him), and to forget that he only spent a few days making them and what we are hearing is barely (90 minutes) of his life,” he writes in the introduction.

Coincidently and serendipitously, Lauterbach and Anderson met to work in the manuscript on May 8 (Johnson’s birthday) and Aug. 16, 2018, the 80th anniversary of his death.

Anderson was 12 when Johnson died and he was a come-and-go presence in her house (her father had been married to Johnson’s mother, Mama Julia) so her memories are either stories told to her by others or potentially clouded by time.

Still, it’s beyond gratifying to hear remembrances from the only living person with first-hand knowledge of Johnson, whom for many is a specter defined by scratchy old recordings and apocryphal stories about selling his soul at the crossroads and playing with his back to the audience so they couldn’t learn his Devil-begotten skills.

Anderson’s Johnson is a fun-loving guy who played Jimmie Rodgers songs and children’s tunes on his guitar when he wasn’t off “hoboing” with Brother Son – Anderson give everyone an honorific title.

She doesn’t know if he was a hard drinker or if Johnson was poisoned by a jealous lover – “I didn’t have him in my pocket,” she says repeatedly. But Anderson does know who the real Little Bernice in “Walking Blues” is and some of the songs Johnson played after the Joe Louis-Max Schmeling bout on June 22, 1938, which wound up being his final Memphis performance.

These are the moments that make “Brother Robert” worth reading.

At 224 pages and with a generous helping of photographs of the ruins of places Anderson writes about, Brother Robert is a quick read and only partially about Johnson when he was alive. The balance is fleshed out with quotidian details about life in segregated Memphis in the early 20th century and Anderson and her family’s unsuccessful efforts to access royalties – from Johnson’s recordings and those by Led Zeppelin, Cream, et al. – a half-century later.

Much of this, and a lengthy interview with Anderson that rehashes the main narrative, is a slog.

But Brother Robert is the closest readers are ever going to get to Johnson sans myth. And even if some of the information is questionable because of the passage of time and Anderson’s young age at the time of the events described, it’s far more interesting than the crossroads bit.

Then there’s that priceless cover shot.

No Comments comments associated with this post