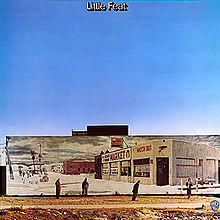

The debut album

Jagged cut to Southern California: The famous LA haze could not obscure the confounding wreckage of tangled freeways, human lives, nor the anvil hanging over one’s psyche of potential disaster from the San Andrea’s Fault, which rumbled and shook the ground from time to time as a reminder that we were living on borrowed time. The noise and anarchy of Southern California resembled a fifty-car pile-up on the famous Grapevine, during an impenetrable fog. There was a “the dogs run free why don’t we” attitude led by Kim Fowley and his crazy crew of psychedelic adventurers. Fowley was part of Frank Zappa’s Freak Out album that heralded a break with the previous generation.

Frank had it right. LA was not cool. It was full of plastic people. But who cared? People, plastic or not, were living on the fringe at a frenetic pace and there was no stopping the tidal wave of youth claiming their territory.

There was the lemming-like migrations to the Sunset Strip. Cruising down the Strip on a sunny day, the top down, one could almost hear the faint strains of “Kookie, Kookie, Lend Me Your Comb,” echoing off the nearby canyon walls, residue from a less complicated era. And at night, Gazzarri’s, Pandora’s Box, The Whisky A Go Go, and further off the Strip, The Troubadour, where the hip and curious met, crushed together like sardines, some dancing like a load of laundry in a washing machine at slow cycle, while others on the outside fringes drank, smoked pot in the corners, shutting out the world of freeways and congestion for another type of congestion that involved touching. LA is a city of cars, creating a bubble between you and them, and no matter that you could walk somewhere, you always drove. The clubs were where you had contact, real contact with others. The promise of sex filled the air. Free love was not a slogan any longer. People would just as soon fuck as shake hands. Valley girls liked having sex, their underarms and legs sculpted smooth. That was Southern California, complete with bronze surfer dudes and dudettes, Everybody’s going surfing, Surfing USA.

The thread that held everything together, while conversely threatening to rip everything apart, was music. There was a revolution in the works fanned by FM radio. In Southern California you had KMET, KMPX, KLOS, and the DJ’s that pioneered the free format: Tom Donahue, Jim Ladd, B. Mitchell Reed, Jeff Gonzer, Dr. Demento, and many others, where one could immerse themselves in the best of what we now look back on as a truly Golden Age in music (Rock & Roll, Blues, Jazz, Folk). This free format stoked imaginations, gave a true sense of community in a part of the world that seemed devoid of any such concept, creating a soundtrack to people’s lives while providing context to events both local and global. The very basis of this experiment was to expand the idea of freedom and test the boundaries of authority. The Vietnam War and the attendant Draft drew the lines of demarcation between those pushing those boundaries and those who felt strict adherence to control of morals and duty to country. A collision course was set in motion like a huge wave hitting a jetty, the result manifest in the Sunset Riots. Nationally, the War protests, along with the Race Riots in 1967, fomented the Law & Order crowd Richard Nixon wielded into a political and philosophical base two years later—whose reverberations are still being felt today through the voices of Palin, Beck, Limbaugh, and Fox News.

What made it all so surreal was the lifestyle associated with the California experience, that still captivates people from around the world—sunny weather, fast cars, fast women, movie stars, the Pacific Ocean, and the varied landscape of mountains, beaches, and deserts.

Iowa and Hollywood might as well have been two completely different planets. And there was Richie Hayward in the middle of it all with a rage in his heart and mind that never really cooled out until he became ill some forty odd years later.

For those that knew him, saw him play, think of the motion in which he attacked the drums. A flurry of arms and legs, mouth opened, eyes wide open, a blur of sound and fury coming from cymbals, snare, toms and kick. It seemed that he could go off the road at any moment, crash and burn. That was the exhilaration of style and substance he brought to his playing, his life. It enamored many, frustrated and angered more than a few, was truly a marvel to witness, and left me more than a few times scratching my head wondering what the hell made him tick.

The Blur Begins

I met Richie summer of 1969. It is an absolute fog for me as to where I met him. Lowell George might have arranged for us to tag up the first time at a club around the Melrose area in Los Angeles—Lowell lived in Los Feliz, not too far away.

The club was dank, dark, and weird. There couldn’t been more than five people in the place. I have no recollection of a band playing there, although I’m sure there must have been some music going on at some point. What I do remember is seeing Richie and the two of us laughing about a guy that was semi-hidden in the recesses of the room moaning in a Droopy the Dog cartoon voice, “This is baaad, verwee, verwee, baaaad!!” He would quiet down for a few moments and begin the mantra again, always with the same inflection. And though we were laughing, there was a point where with arched-eyebrows Richie suggested we get the hell out of there. It was indeed, baaaad, verwee, verwee, baaaad! For years we talked about it wondering what the hell the poor guy was going on about.

Not too long after that we met again at Lowell’s, Richie set up his drums and the three of us played some various songs and riffs. Nothing particularly coherent. I loved what I heard, though, coming from the drums, which is to say I had never heard anything like it in my life. Not as polished as Keith Moon or Mitch Mitchell, but we weren’t in a recording studio, we were in Lowell’s living room. Lots of cymbals, a wild kick drum and plenty of toms. Later, after he left, I asked Lowell if he was going to be in the band—we were in the process of putting players together for what would eventually be Little Feat (the name was either non-existent or up in the air at that point in time). Lowell told me that Richie was with the Fraternity of Man (“Don’t Bogart That Joint”) that played some prominence in the icon movie, Easy Rider ). I said, “Lowell, how can he be in that band and be in ours?” He said, “Don’t worry, you’re going to play on their record and then they’re going to breakup, Richie will then join us.” Welcome to Hollywood!

The first year was spent looking for a record deal. We were approached by several labels, including Atlantic Records, where the President of the label, Ahmet Ertegun, after hearing our musical offering merely said, “Boys, it’s too diverse.” We jettisoned those songs shortly thereafter. Along the way we auditioned at least fifteen bass players at Lowell’s house, of which Paul Barrere was one of them—Lowell knew he played guitar, yet told him, “Don’t worry, the bass only has four strings.”

With a new lineup of songs, we finally approached producers Ted Templeman and Lenny Waronker from Warner Bros., this time successfully, which paved the road for bringing in the bass player we had wanted all along, Roy Estrada, from Frank Zappa’s band. He had been sitting on the sidelines waiting to see if we could land a deal or not. That said, Roy was a hero to me. The four of us journeyed into the beginning of musical history with Warner Bros. Records as our stewards.

Take a look at the old photos of Richie. He could’ve been a movie star. The mustache took on a D’Artagnan quality. Swashbuckling. Richie always had access to some great hats. On our first album, Little Feat, he is wearing a top hat taken from the Warner Bros. lot, I believe. They let us rehearse there in Burbank. There was a huge box with all kinds of hats in it, and, well, Richie took his pick. It fit him in every sense. For the album cover, we stood in front of a building in Venice, CA., of which was a winter scene painted by the L.A. Art Squad, featuring what Venice might look like if another Ice Age hit—no one was mentioning Global Warming back then, although it was nearly ninety degrees that afternoon and we were dressed in big overcoats and winter hats. Out of all of us, he was the only one of us with any style for the occasion. It didn’t occur to me that Richie was the only one with any real experience for winter, having been raised in Iowa.

The memories I have, many of them, are fragmented, especially from the early times. It was such a free-for-all back then. Paul, Fred, and I were talking with Mac Rebennack (Dr. John), one night in Clearwater, FL, about the craziness of those times. Mac offered his condolences. Earlier, before Paul and Fred showed up, he told me he had lost four friends in the space of less than a week. Life was moving fast. There was no doubt we lived through a remarkable time period, he said. It was all brand-new, and, in many ways, uncharted territory. I told Mac that when we joined Warner Bros. in 1970 the roster included him (Mac was actually with ATCO, which was part of the Warner family), Ry Cooder, Van Dyke Parks, and Randy Newman. I was absolutely floored that we were in that kind of company. It was a period of genuine financial help from the music industry. Warner Bros. funded our first tours, for example. Touring was a channel, as much as having a hit record—which Little Feat never had—to reach an audience. Live music. Real players. We were in heaven, and hell, as it turned out. This is where we really got to know each other. On the road.

No Comments comments associated with this post