JPG: You started playing drums at the age of five. So, you’ve been addicted to music for quite a long time.

RXH: Definitely. A whole lifetime.

JPG: Do you remember the very first song or the very first conscious moment where something clicked with you?

RXH: First, there was the big band jazz because that was being played in our house. So, those were the earliest memories of hearing Gene Krupa play with Benny Goodman. But my first real rock ‘n’ roll recognition was hearing “Uptown” by the Crystals. I had three older sisters and occasionally they would go to the hamburger stand, these drive-ins, back then. Every now and then, they would let me tag along in the back seat to be with their boyfriends. I would be in the backseat of the car as a little kid and I heard “Uptown.” I was sitting there and the speaker was right behind my head and it was absorbing the song and it just really had this emotional impact. It was just one of those recognitions when, ‘Boy, I love music!’

And then I remember hearing “Wake Up Little Susie” by the Everly Brothers. That hit me hard, too. Every time I’d see the Everly Brothers were going to be on TV, it was always a big thrill. The anticipation that they were gonna be on TV. I just loved their pompadours and, of course, their great harmonies.

JPG: I’ve read that your music is even influenced by Broadway musicals as well as hearing everything from British invasion and Beach Boys and so much more in there.

RXH: When I was growing up, my parents would take me to see Broadway shows. We lived a half hour outside New York City; just to go in and see all these first run great musicals. Just hearing the pit band would be so exciting for me. I would always run up and look in there to see the drum set. Always a big thrill.

JPG: All of that has become a part of your musical DNA. It just seems to flow out so easily.

RXH: It’s always nice to soak up all of these influences and then, hopefully, it comes out the other end as something original out of all that. You can hear the influences in there, but it’s not derivative. That’s always the best combination.

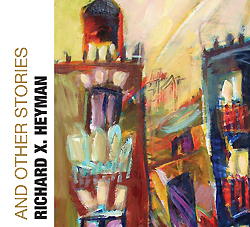

*JPG: Can you think of a moment on “Tiers” or the other album “And Other Stories” where such an influence consciously came to you, maybe where you’re stuck and you think, ‘Oh yeah, Paul McCartney did it this way on this, why don’t I try this kind of arrangement.’ *

RXH: I don’t really think that way, more in service of the song. I’m so emotional about music. I think more in terms of the way it makes me feel more than how did somebody do it back then. I will say that when I’m singing there’s always my favorite singers, how to compartmentalize with my brain. So you’re going for a certain note or a certain line, you might think Stevie Winwood in here. I might think McCartney or Lennon here. I might think Dylan here. There’s that little connection because those are your influences. That’s what you grew up. You pick out your favorite singers and they’re all in the back of my head. As I’m doing a performance I might subconsciously go for a stylistic slam dunk. As far as general arrangements, my feeling is what emotionally is going to work more than how the Beatles did it. Maybe that’s in there, but I don’t really think about it.

JPG: Just curious, since your multi-tracked and harmony vocals evoke that pure pop ideal do you have some idea of your vocal range?

RXH: I just know that my speaking voice is a little high. I have more trouble with low notes than high notes. I’m always changing keys to get the best possible range. As far as high notes and the like, I can scream out a “B.” If I had a gun to my head, I could probably scream out a high “C.” Low notes drag me out. I’ll probably be the only singer in the world that does songs higher live than the recorded versions. Not everyone, but a lot of them are 1/2 step or a whole step higher than the recorded version just because live I need a little more of that push to hear over the band.

JPG: Because you’re singing in a higher range, I think that adds to the brightness and the sunny qualities of the songs.

RXH: One can only hope. Sometimes when I’m recording, I’ll put a song in the lowest key that I can possibly do it because I feel that the song might sound better with a little more of that somber quality at the low part of my voice, the baritone part rather than the tenor part. I don’t know, I am somewhat weird between, not really a true tenor, not really a Baritone. All that in between.

JPG: When I see the lengthy list of instruments you played on the albums and I hear your vocals multi-tracked, it makes me think of Todd Rundgren doing all the work on a number of his releases.

RXH: Oh, yeah. I started doing one-man band things like ’69/‘70, right around when McCartney first came out with his. I started doing it because I was working at a friend’s studio. He had a four-track. Being a drummer, I just naturally decided to put down the drums first and build up the track. I started getting proficient enough on the piano to be writing songs and putting chord progressions together. I was doing it back then but none of that stuff ever got released. But I happen to have it all. They’re not bad. Developmental. You have to start somewhere.

JPG: If the Stones can go back and pull old tracks and patch ‘em up for a new album, you could, too.

RXH: I have this album, Actual Size, where I went back and picked a lot of my earliest songs and re-cut them. Put that out a few years ago.

JPG: When Rundrgren was doing that type of thing, were you like, ‘I was doing it and now he’s getting all the credit?’

RXH: I thought it was a goof. If I hear music that moves me, I’m not really that concerned and impressed with the way it’s done as much as the end result. That’s how I feel about my own stuff. It doesn’t matter to me, how it was done. How does it feel when it’s all said and done is really what I care about. There’s this romantic view of the path to creating music, which is fine. Makes great stories. Some people are real sticklers for methods. They want to keep things pure. I respect that. I just don’t care about those things. Whatever it takes to get what I need.

In country music, they call the capo (a clamp fastened across the strings of a guitar to raise the tuning) the Cheater because you’re slapping this thing on the guitar and it’s making it easier to play on different keys. Now, it’s just an established way of playing the guitar. If you write a song that’s an open string ringing, you don’t want to lose that just because you changed the key. So I look at everything like that. With all the modern technology, I will say, I don’t use any sort of harmonizer or pitch correction because I don’t have those things. I do all of that the old fashion way. But it’s not because I believe in the purity of it. I could have those things and don’t know how to work them, yet.

No Comments comments associated with this post