Ahh… another transitional era for the Grateful Dead. Indeed, this was an early and critical turn away from the San Francisco rock band’s heavy psychedelic period. 1971 marked a continued focus on songcraft, begun in 1970 with the twin studio masterpieces American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead, and cemented by the 1972 solo debuts of Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir. Whereas, Garcia’s album was more of a solo set in the classic sense, and includes some of the cream of the Robert Hunter-penned partnership with Captain Trips, Weir was backed by the Dead. But a growing confidence was developing, and proved crucial for his songwriting and frontman development. Weir, as well, had a solid lyrical partner in John Perry Barlow, and their union would prove to be most bountiful.

Actual songs were being introduced in the Dead’s repertoire, with timeless stories, featuring a variety of American nowhere men—lost, confused, and, perhaps, defeated. The band was also leaning into a bend in the road leading to the spectacular soundscapes from 1972 through 1974 when the Dead were improvisational kings, and Keith Godchaux sat in the keyboardist’s chair during their most creative period. Which brings up Ron “Pigpen” McKernan. Ill from years of alcohol abuse, Godchaux was asked to join the band during Pigpen’s recovery efforts. Slowly, tragically, the formidable frontman, who had once led a dopey blues band, who happened to find their way into outer space, would fade away due to his condition. McKernan died at the age of 27 in early 1973.

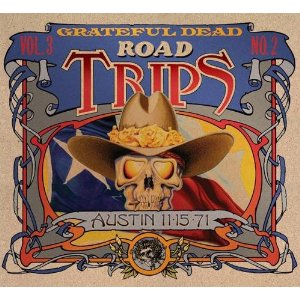

The latest edition in the Road Trips series picks up a month after Godchaux joined the Grateful Dead. The quintet is still working their way through new and old material with the keyboardist. Whereas in the past, the Dead would go off on various weird tangents within somewhat of an abstract framework, in the fall of 1971, they were solidifying their two-set structure, and honing down on what worked, and what didn’t. Of the two sets from this show from November 15, 1971 in Austin, Texas, the first has the hardest-hitting, and, dichotomically, the most exploratory material. Alas, both sets contain only rare glimpses into a new area of improvisation.

Therein lies a small problem. While the band is working their way through a dynamic opening duo of “Truckin’” and “Bertha,” they are also trying to shift gears in a rather rote “Playing in the Band,” which neither jams, nor ascends into any semblance of space. That would happen often in 1972, of course. Not here. “Deal” and “Loser” make appearances from the aforementioned, soon-to-be-released Garcia solo album, and are still embryonic, as is “Jack Straw,” which hasn’t acquired its potent gravitas just quite yet.

But the rare first set “Dark Star” finally lifts the band into interstellar overdrive, and actually reaches some extraordinarily beautiful passages, a hallmark of some of the earlier ‘71 jams, as well as what was to come in ‘72. The first part of an ill-advised “Dark Star” sandwich drifts along into one gorgeous sequence after another. Garcia leads the way, bassist Phil Lesh both anchoring and offering new directions. Weir is underneath it all, pulling and pushing the band into other areas, while lone drummer Bill Kreutzmann accentuates and propels, and Godchaux, without any effort at all, is at one, almost immediately, with the group mind. If there is a consistently fascinating aspect to this show, it is the fact that the entire band sounds solid, albeit somewhat restrained due to its new band member; ironically, however, it is Godchaux who seems more than willing to reach out to the new sonic frontier.

And that was the key. Because if he hadn’t, if Godchaux had come in knowing all of the Dead’s material (which he did, being a fan, and a fine musician), and just attempted to play along with the thundering herd, the Grateful Dead as we know them, may have passed away along with Pigpen in 1973. It is interesting to look back on the fall of 1971, and hear that subtle tension between what was, and what could be. Somehow, they found a way back into space, and there is critical evidence of how they were going to do that, and what they needed to jettison, on this release from November 15, 1971.

Ahhh…but we digress, and find our way back into “Dark Star.” The Grateful Dead being the Grateful Dead segue out of “Dark Star,” and into Marty Robbins’ “El Paso,” which, of course, can be foisted upon Bob Weir, since it is his selection of a cover, but the entire band joins in, before eventually returning to the space of a second section of “Dark Star,” which picks up where it left off for a further seven minutes-plus of essential listening. “Dark Star” being “Dark Star,” the Dead find a way to that odd little bit of twisted magic again.

The second set could be called their Cowboy Music showcase, or the “Texas setlist,” with everything from “Mexicali Blues,” to both “Me and…” songs (”…My Uncle” by John Phillips and “…Bobby McGee” by Kris Kristofferson). But “Cumberland Blues” finally kicks the door down. Later, the real Dead steps through with an extraordinarily unique version of “Not Fade Away,” which segues into a jam based on nothing at all but what the transcendent moment has offered. Jerry Garcia’s every exquisite note seems to be chosen from some other cosmic place, and then he melts everything into the theme from “China Cat Sunflower,” brings the band down to a quiet slice of the Great Unknown (a ‘jam’ jam during the transition between two songs when none like this has previously occurred, AND with a new member?), before Godchaux pushes Garcia and Kreutzmann to challenge Lesh along the shore of the beat, cascading and gliding with each other in a parallel race, before dropping into a volcanic “Goin’ Down the Road Feelin’ Bad,” which ends up in a “Not Fade Away” reprise.

The Road Trip series has included some bona fide gold in the bonus discs in these editions, and volume 3, number 2 is no different. Included are several nuggets from the evening prior, November 14, 1971 at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth. Specifically, the band cooks on a rollicking and rambunctious sandwich—“Truckin’ > Drums > The Other One > Me and My Uncle > The Other One > Wharf Rat > Sugar Magnolia.” Yes, the sequence is as tasty as it looks, and, yes, again, to this writer’s ears, the what-the-fuck factor is in full-on mode when listening to “Me and My Uncle,” arching its inconsequential head out of an otherwise colossal “Other One” monster.

No Comments comments associated with this post