Some binge-watched entire seasons of television series or made sourdough bread when life was paused due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Others either lost their minds or found the lack of social activity as a time to reassess their lives.

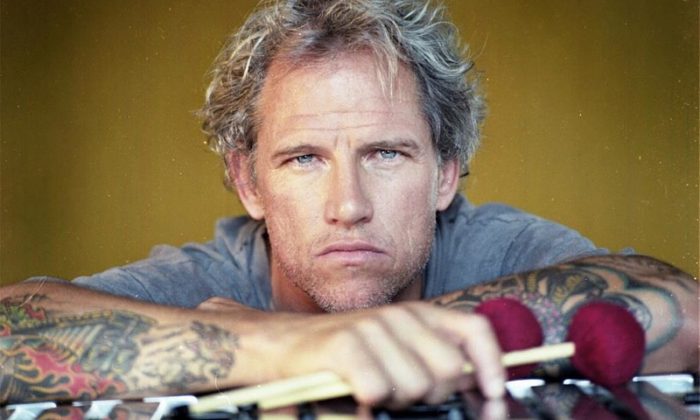

For Mike Dillon spending time off the road in 2020 could have been devastating. After more than 30 years performing over 200 shows a year with his band or playing vibraphone and percussion with Les Claypool, Ani DiFranco, Rickie Lee Jones and others, it was a difficult adjustment to stay at home rather than crisscross the continent once more.

“My tour ended on March 8th,” he said during a recent interview. “I remember I got back to Kansas City, Galactic was supposed to come to town and play, and I was going to play with them that Friday. Everyone’s watching the news. Next thing I know I get a text, “Tour’s been canceled. We’re not coming.” By that Friday, everything had been locked down.”

Rather than give in to his dark side, he focused his creative energy and used it as an opportunity to record and record…and record some more. When he was finished, Dillon had completed three distinct projects.

He describes “Shoot the Moon” as “Punkadelic-Funk-Psych” that targets the United States political climate. The material features Matt Chamberlain, Steven Bernstein, Nicholas Payton, Robbie Seahag Mangano, Jean-Paul Gaster and Nick Bockrath among others.

On “Suitcase Man” Dillon examines his life and choices made over the past 55 years. Influenced by one of his favorite musicians, Elliott Smith, it’s marked by honest lyricism and minimalist arrangements.

Finally, “1918” focuses on Dillon’s instrumentals — the Moog/tabla/vibraphone psych vibe of “Pinocchio,” the electro analog trance of “Pelagic” and the jungle groove, space rock of the title track. Thematically, the songs address the Covid-19 pandemic and recent social unrest. “The parallels between 1918 and 2020 are immense. We just have fancier toys, but the tunnel vision and mammalian tendencies are the same if not greater,” he said.

In collaboration with his longtime record label Royal Potato Family, the releases were offered exclusively on Bandcamp days after they were mixed and mastered. Then, earlier this year, they came out simultaneously on vinyl as well as made available across all streaming outlets.

A native of San Antonio, Texas, Mike Dillon got his start as a sideman, playing in such varied projects as MC 900 Foot Jesus, Brave Combo and Secret Chiefs 3. He’s also served as an integral member of bands like Critters Buggin, Garage A Trois, Dead Kenny Gs as well as leading Billy Goat, Hairy Apes BMX and Malachy Papers.

After 15 years in New Orleans, I find the open and talkative Dillon at his new Kansas City homebase. Our conversation takes place prior to his wife’s truck and airstream getting destroyed by a driver in a stolen vehicle. Of course, road warrior that he quickly returned to the road, while a GoFundMe campaign raised enough money for a new vehicle and caravan.

JPG: You’re back in Kansas City?

MD: Yeah, I’m sort of… I’ve been in Kansas City a lot, but I’ve been in New Orleans a lot this year. I got a good friend, he’s hooked me up with an apartment down here, so…New Orleans will not let me go, and I won’t let it go, either.

JPG: If you don’t mind, what brought you do Kansas City? Why not just stay in New Orleans full time?

MD: The lady I married.

JPG: Well, that’s a good reason.

MD: That was the catalyst for…right before the pandemic started, they threw us out of the apartment complex a lot of musicians have lived in over the years. My buddy Doug Belote was living there, great drummer, Brian Blade, who lived there, Seth Walker. Seth Walker and I shared an apartment there for awhile. Then, he moved up to Nashville full time, so I took it over. August, September they were like, “New owner.” They gutted all the apartments, made them fancy and took them from $600 a month rent up to $2,000 a month.

So, when the pandemic hit I was like, “I’ll just stay [in Kansas City] full time for awhile. Move all my stuff in here.” I had everything in storage in New Orleans until June of 2020. That’s when I went down, finally got my stuff. A lot of my instruments were already in my van. Some of them were already at [artist/photographer] Peregrine Honig’s house. Pretty much all I have are instruments and a few pairs of black t-shirts that people give me along the way.

JPG: Last time we talked was in 2011 about The Dead Kenny Gs and Garage A Trois albums because they came out at the same time. Now, you’ve gone with the release of three albums at once. What was the thinking behind that?

MD: What happened was, Kansas City’s important to it. I lived there during the Billy Goat years. When I’d go to Kansas City and hang out I would just write music and play a couple gigs here and there. My friend who I’ve made records with over the years, Chad Meise, tons of stuff going back to the mid-’90s with him.

When I was up there hanging out with Peregrine, it would be like, “I’ve got this new song. Let’s record.” So, that had been happening. That was how “Rosewood” happened. I got Earl Harvin from Billy Goat…he went on with Seal after Billy Goat, and he played with Richard Thompson and MC 900 Ft. Jesus. Lately, he’s been playing in this band called Tindersticks. He lives in Germany. He’s like one of the top drummers over in Europe now and plays with J-Lo when she goes to Europe. I got him to come in and play on that with me.

That was about to come out and then the pandemic hit. For the first two months, all I did when I was off the road was just sit around and write music all the time. There was literally nothing else to do. It’s either watch Netflix or read a book or…and I really got into livestreaming. That was really fun. I’ve been working on a solo one-man show, trying to figure out drum machines and different things. So I was like, “Alright. Here we go. Sink or swim. Let’s do this.”

The by-product of it was I started writing a lot of songs just for the livestream. Then, I had all these ideas I’d been messing with. Starting about December of 2019 I had a little two-week break, and I started writing a bunch of stuff. As soon as that tour was over I’d done two months, from like December 26th, 2019 up until March 7th. That was the last date of the Mike Dillon Band tour. We were calling it Punkadelic by that point. And then, boom, everything gets shut down. I think it was around top of June I was like, “Hey Chad, you want to start recording?” He’s like, “Sure, man, we don’t even know how we’re going to keep the studio open.”

I’d got a little bit of royalty money from one of the bands I’d worked with, and there was the livestreams, and finally in the middle of July some unemployment kicked in, so I had enough money to make some records. It was like I’m just going to take all of my livestream money and give it to the studio. It kept them alive, and it really was amazing that way. I was like, “Fine. I can live off my unemployment and give all my livestream money to Chad and keep the studio…because he wasn’t getting any unemployment. We just started going to the studio all the time.

So, it was really just timing, too. I had 30 songs that I wanted to record. At the time, I had no idea of putting them out or anything. Just like, “There’s nothing else to do. Let’s record.” And we’d drive around with it for a few days and be like, “Alright, let’s come back in.” Then, friends like Matt Chamberlain and Earl, who I just got through telling you about, I started sending them tracks because that was the idea. “We’re all at home. No one’s on the road. Here’s a track.” I made a session in Dropbox called Quarantine Boogie Sessions and people started sending me things and Chad and I would put them together.

It just kept growing. He was like, “Man, we ought to get a guitar on this. Someone that sounds like Captain Beefheart.” So, I called Robbie Mangano, he goes by the name Seahag — he toured with Rickie Lee Jones with me — and he started doing a bunch of stuff. Then, my longtime bassist, Nathan Lambertson, he’s like a boy wonder with perfect pitch who can hear any of the nonsense that comes out of my improvised style of writing and play it in two seconds. I would send him stuff and he would do some synth stuff and bass lines. Sent one to JP (Jean-Paul Gaster) from Clutch. He did a track for me.

It was so much fun getting all this collaboration; the whole idea being instead of when you’re in the studio and you got a week of time booked or three days booked, it was like this is open-ended. No one’s going on tour tomorrow, so let’s just take our time, whatever you want to do, do it and we’ll see if it works.

Bernstein, the track he played on [“Further Adventures in Misadventures”]. I went in one day and on my big giant bass marimba started doing this thing. I don’t even think I recorded it to a click track. Then, I went in the studio and put another marimba track on it. Then, a tabla track. And I sent that to Matt Chamberlain. Within a day, he sent it back to me. It was amazing because on my end, there were flubs but he’s such a studio madman — records with all kinds of people – he just nailed it. All of a sudden it became this weird, almost 6/8 African Konono Nº1 piece like we used to do in Critters Buggin.

A week later, I was talking to Steven Bernstein. He just called me up out of the blue because he did a lot of that during the pandemic, just call people and talk to them. I was like, “By the way, I got this track. You want to play on it?” He’s like, “Yeah, Dillon, I’ll play on it. Are you in a hurry or is this wide open?” I’m like, “Man, it’s like Brian Eno and David Byrne. Whatever you’re doing.” He’s like, “Cool.”I didn’t hear from him for a month or two and the records are all being developed. All of a sudden he’s like, “I’ve been working on this thing for months.” And I’m like, “What?!?!?” He sends it to me and he’d done a slide trumpet choir. He had this time to do all this stuff. Bernstein’s flying to Europe every other week when he’s not…He had time to work on things that had been in his head.

So, I think for a lot of us it was just a fun way to be creative during this really strange, bizarre time that I feel like we’re finally starting to come out of.

JPG: While a lot of people had trouble over the past year because they were stuck at home, or in cases of musicians, unable to tour, you found a positive outlet. You weren’t losing your mind that you weren’t on the road…or were you?

MD: I definitely did lose my mind. Not to bring up my addiction history but that’s how I dealt with addiction was instead of my life being ruined by it…it’s almost like that Burroughs quote, “You have to write your way out of it.” So, that’s always been my biggest medicine — writing and practicing and playing music all the time. There were times I definitely started losing my mind like everyone else during the pandemic. It wasn’t for reasons because we were not touring. It was just other emotional weird things that I think everyone had to face something intense.

Creativity and gratitude have been my two biggest antidotes to self-destruction. So, for me it was like I had no choice. I think a lot of artists are that way. Unfortunately, on the other side of it, besides all the people we lost from COVID, the mental health toll has been astronomical. They’re not even talking about that enough. I know several people that…and even in the recovery world, a lot of people relapsed and died. It’s been a hard time for a lot of folks. I definitely have a strong community of friends in that world, that are musicians and that are recovering addicts and we were all there for each other, doing Zoom things and not necessarily even 12-step stuff. Just, “Alright, we’re going to do this. We’re going to keep it positive.”

And it was awesome. You got some people I look up to that are in the same boat. We’re alright. We’ve got to stay positive. Quite a few musicians that I talked to, they were just like, “Wow! I realize what it’s like to be home with my wife for a year straight.” For me, I really realized that I’ve been stunted emotionally and that I have no concept of being… because I’ve been on the road for 35 years, since touring Texas — maybe even longer than that — but touring Texas since ’86. Then, in 1990 we did our first Billy Goat tour up to Chicago. On that first Billy Goat tour we played Stache’s in Columbus and we played Lounge Ax in Chicago, and we played a little club called Hangar 9 in Carbondale, Illinois. Then, the Bottleneck in Lawrence, Kansas. Those five. It was like, “Wow, I got a tour and I booked it!” Then, I was like, “Wait a second. Ohio, Chicago, Carbondale, back to Lawrence, and then home.” It was a funny tour but that’s when the bug bit me. That’s all I wanted to do. Tour and tour and tour.

JPG: So, basically, you had to, as the minutemen said, Jam Econo.

MD: Exactly! Yeah, my first van that we toured in was a Ford Econo. And it was exciting because I didn’t even realize how lucky I was. We opened for fIREHOSE a couple times back in the ‘80s and just seeing [former minuteman bassist/punk legend Mike] Watt pull up in his Ford Econo van…!

“Alright, I’m now 55 and I’m going to learn how to live at home and have a normal life and…” Definitely the financial fear for me was the biggest thing, because I’ve been living hand-to-mouth for all these years. I’m pretty used to it. “Got gigs booked, the bills will get paid. We’re cool. Let’s go!” And it’s always worked out. “Alright, cool, a good gig came through. That’s going to make things a little easier.” That’s the way a lot of us were working.

When the pandemic hit the financial fear for a lot of us musicians all of a sudden our work was taken away was tangible and real. The hyper-cool thing is the fans…I did my first livestream and the donations in the tip jar was incredible. Everyone was so nice and giving and people still are. It leveled off. It was up and down. And, believe me, I know our livestreams at the beginning were horrible. Poor wi-fi on our cell phones. There were all kinds of things to learn. But, in a lot of ways, I know we were blessed because the fans supported us and got us through this. Totally couldn’t have done it without them. They’re the ones who keep us fed, no matter what.

There’s bands touring all the time, and people go out and buy t-shirts, buy records, pay a cover. I’m really grateful for all the years of people coming out and supporting live music. Not just my band but all the other bands they support. It really is about them.

JPG: With the recording of the three albums. You were in the studio but everything else was sent to people. You were trading files online.

MD: That was all via Dropbox or WeTransfer. Luckily, a lot of my friends have great studios. They would send it to Chad and he would put it together. At first, I wouldn’t even go in the mixing room. We stayed masked up. He stayed in the control room. He would activate the back door. It would open. I’d bring my stuff in. I would do my part. I was the only guy there. In August and October, Go-Go Ray from Billy Goat came in and played some live drums with me. We did the first song on “Shoot the Moon” together live, he and I. Then, J.J. [Richards] was able to come by when he was in town in October. Hairy Apes BMX. He played bass on a few tracks and sang some background. But everyone else was remote. It’s pretty amazing that it all lined up and sounds as good as it does. I’m really proud of these records.

JPG: You have good reason to be proud of them. Releasing them all at once now gives a thematic sense about the releases. Still, I’m a little surprised that they weren’t spread out on different dates.

MD: Originally, I put them out on Bandcamp. It was that free Friday thing. (Bands got 100% of profits). Just like everyone else, we were all trying to hustle and monetize. Make a little money any way we could. So, we released the first one in October, “Shoot the Moon” and then “Suitcase Man” in November.

Kevin [Calabro] from Royal Potato Family Records, didn’t even know I had a third one. He didn’t even know I had “1918” in the bag. “1918″ happened because I had all these tracks that didn’t make “Shoot the Moon.” I knew right away what “Suitcase Man” was going to be. I was like, “That’s going to be all the “Suitcase Man” songs. Just vibes, marimba and vocals.”

For “1918,” when I put it out…a lot of people really liked that record. It was funny because that was the one that I put together last. I recorded a few songs for it in December in the studio. That one almost had the spirit of the old records, two or three tracks. It was like, “We’ve got to hurry. I got this new song and Bandcamp free Friday is this Friday. Can you get it done?” And Chad’s like, “I’m mixing at the Latin Grammys in Florida but I’ll be back. I’ve got to quarantine. I’ll get it done for you,” and he got back and got it done.

Then Kevin, we’re talking, and he’d already said he wanted to put out “Suitcase Man” on vinyl. We were working on the packaging. And “Shoot the Moon” as well. After he heard “1918,” he goes, “What do you think if we put all three of them out?” I’m like, “Really? Well, do we want…” Just the same question you asked. Do we want to spread them out? And he said, “No, why don’t we put them out all on one day?” And I was like, “Yeah, that’s pretty badass.” It definitely made a statement.

It’s funny. We’ve been playing them the past two weekends, did a show in Denver and some shows here in New Orleans and it’s really hilarious to be able to go, “And this is the first song from my first record of my three records, which were released on Friday.”

JPG: I like “1918” the best out of the three. I don’t know if it’s the instrumentals that I dig more or the vibe of that album but it’s interesting that you almost didn’t put it out.

MD: Almost didn’t put that record out, and now, when I hear it, you’re absolutely right. It encapsulates a lot of what we were all going through emotionally. Some of the songs that are instrumental really speak to me louder about the whole emotions I know that was feeling than the lyrical content. That’s the cool thing about instrumental music. It provokes a feeling in the listener but you don’t have the lyrics saying, “This song is about…” whatever it is. It lets whoever’s listening to it paint their own enjoyment.

JPG: Now, for “Suitcase Man” and “Shoot the Moon,” did you have the themes and the subjects set up before you did them or did they develop?

MD: “Suitcase Man” was definitely very cohesive. I was like, “Okay, I’m going to do a singer-songwriter record but instead of using a guitar I’m going to play my vibraphone and the marimba. And in the spirit of those Leonard Cohen records I love, I’m just going to have a couple of background singers make my raspy voice sound a little bit more tolerable. I’m going to do something I’ve never done before. The impetus was recording an Instagram video of “Suitcase Man.” That was the first song I wrote for the record. We wrote that song in five minutes, I started the initial thing, and then Peregrine, she took it and she made a few changes, added a few lines here or there. When we recorded, it was the most liked Instagram video I’d ever done. And it got a decent amount of views.

People that I look up to like Anders Osborne and Ryan Montbleau and Bailey [Smith] from New Orleans punk band Morning 40 Federation and Clint Maedgen from the Preservation Hall Jazz Band, they were all very complimentary [of “Suitcase Man”]. Clint and I share this insane love for Elliott Smith. I’m obsessed with him. So, it was almost like me having my — I’m not going to say me wanting to be Elliott Smith — but just I love that kind of stuff. A lot of people are surprised to find out I love singer-songwriter stuff but I toured with Rickie Lee Jones for years. I still work with her. I have so much respect for people that sit around and craft every word because a lot of bands I’ve been in, even the vocal bands, you come up with the jams, the riffs and then the lyrics are the hardest part. I like to make things abstract and weird, and I think that’s why a lot of people compare my music to Claypool and to Primus when they hear me.

These kids this weekend, “You’re like Primus.” And I’m like, “Yeah, well, I’m like me.” But I love Claypool. It was never an intentional thing to try to be like Les. It’s awesome that I’ve worked with him for so many years. I’m still a big fan of the weird, abstract, Captain Beefheart, Frank Zappa, fucked up music…that’s always going to be in my heart. But for “Suitcase Man” it was like, “Alright, I’m going to go on a limb and really try to put my heart on my sleeve and write something.”

And Peregrine [Honig] collaborated on the lyrics on these three records. Whereas, I’m real abstract and weird, she’s more focused and is a great writer and extremely educated. So, it was great to collaborate with someone.

“Shoot the Moon,” that was just the first one, and those were the songs that I liked first, and those were the ones that I felt had all the best performances from all my friends.

JPG: “Shoot the Moon” was a bit political.

MD: There was a little bit more anger on it like “Qool Aid Man” and a couple of others. That record’s a little bit darker than all the others. There’s a couple instrumentals on there I really like. “Apocalyptic Daydreams,” we’d been playing. But even the titles, it’s like, “Oh… What’s going to happen? Is it going to be complete civil breakdown? Are we about to…? Were the preppers right? What the hell’s going to happen here? We can’t even get toilet paper.”

“1918″ was the resolution of it all. A lot of it started with drum machines in the old church that Peregrine lives in. I had my old [Roland] HandSonic, which is a digital percussion box that has killer sounds in it, and you can make nice loops. I would play along with that. Found some cool things. Then, I got this analog drum machine. I was starting with that. Then, I would either play kit or get one of my friends to play kit over it.

I also bought Ed Mann’s MalletKAT because my vibraphone I play is electric and it’s got pickups on it, and I run it through distortion pedals. Each bar has a ceramic piezo pickup so there’s no distortion. I can run it through whatever pedal I like. I’ve done that for nearly 20 years now. But I started getting into analog synths. I’ve seen Nine Inch Nails five times, probably, over the past 30 years. I didn’t like Nine Inch Nails at all at first then one day I just got it. So, anyway, I really liked his writing process, and in interviews about how he messes with synths. A lot of kids I was touring with, all they talked about were synths. All the guys in the Mike Dillon Band were 20 years younger than me, 30 years younger, and they were just all obsessed with synthesizers. I’m hearing all this stuff. So I’m like, “Maybe I’ll get me a synth now and trigger it with my MalletKAT.”

That was the other thing I got to do. Experiment with my synths and come up with weird sounds. That’s what’s awesome about “1918.” You can really hear a lot of the weird synth stuff I was doing.

I got lucky with “1918″ and how it turned into this concept record. It really worked. It was the concept record that was not meant to be a concept record.

JPG: When you were recording all these songs, nearly three dozen songs…

MD: I definitely recorded over 30, and I definitely had a bunch more that I wrote that I didn’t even end up taking into the studio because it was like, “Wow! I got this giant bed of work here.” That was exciting because I know back in the old days, bands that made great records, they would not just record the nine songs they wrote. They usually had a huge body of work and the producer would sift through it and go, “This, this, this, this,” and compile them to the record. That was what I was hoping to do and maybe that’s what happened with “1918.”

JPG: That’s why box sets come out with all these bonus tracks that got pushed to the side. In your case, let’s see…30 songs altogether. As you were going along, were you saying, “Okay, track seven we’re going to put to the side for “Shoot the Moon.” Track 19’s going to go to “Suitcase Man” or it just worked itself out eventually?

MD: “Suitcase Man,” I knew all the songs that were going to go on there. “1918″ was the leftover because I was like, “’Shoot the Moon’ is going to be the electronic, more rock-y songs.” I just picked out my favorite ones at the time. That’s how that worked out. It’s really weird that “1918,” the songs that in some ways feel the most cohesive together to a lot of my friends are the ones that were the leftovers.

What happened was that when I wrote “Pinocchio” in October, I was down here in New Orleans. I wrote that song in my Airstream and that seemed to solidify the whole record. It was weird that “Quarantine Booty Call” wasn’t on “Shoot the Moon” because I was playing that song all the time. I remember I was going to put “Grandfather Clock” on “Shoot the Moon” but then I was like, “Well…”

What it came down to is I wanted to put more of my rocking songs on “Shoot the Moon” with the vocals. “What instrumentals am I going to put on this? I love “Apocalyptic Daydreams.” Bernstein’s thing on “Further Adventures in Misadventures.” Awesome. And this Afrobeat with Nicholas Payton on doing the weird horn thing on “What Tony Says.” Got to put that on.” Chad helped me pick out those songs.

Those were the ones we agreed on. And then that weird little song, “Dubious,” I’d got back from my first little bit of touring I did, and I wrote that song. Just went to the marimba and wrote it. That song would have really been great on ‘Suitcase Man'” but, ironically, it breaks up “1918″ in a really nice fashion.

We’ve been doing “1918” live and that’s really been amazing because we can do it live. Brian Haas, from Jacob Fred Jazz Odyssey, that’s who I’m touring with. Brian, it’s almost like I wrote that record for him because I jump from the vibes, I have the drum machines going and I’ll play like a little stand-up drum kit, and it works as a duo. And it really showcases his talent. All those songs have been so much fun to play together and it’s a really good setlist. We’ll do that entire record. Start with “Pinocchio,” which is the tabla and the weird Moog-based thing and it just expands. It’s been fun watching the new music grow live and…I’m just marveling at it.

JPG: You played live dates during the pandemic lockdown. How was the experience of performing to socially-distanced audiences or smaller crowds or people with masks on?

MD: What we did was in June. We started in Kansas City at our friends’ houses playing on the porches. Playing outside. By that time there was a lot of us who were like, “It’s fairly safe to be outside.” We encouraged people to wear a mask. I wore my mask at first, even outside, all the time. I was really intense. If you came near me and tried to hug me I was going to hit you. I was like, “Stay back!” The guys I played with would be like, “Oh dude, I haven’t seen you…” Like Brian would want to hug me and I’d be like, “Don’t hug me. Don’t touch me, Brian.” We had done a livestream in New Orleans and it was a weird thing for me because two of the guys in the band were like, “We’re in a room, we’re friends…” One had already had it and then the other guy thought he had it. So, it was like this new dynamic.

The first time we did a livestream together, I wore my mask the entire time. I was pissed that they weren’t wearing a mask. Literally. I was like, “Come on, man. We’re all in this video. We’re streaming. Don’t be assholes. Just put on your masks.” But then they were like, “Well, dude, we wear glasses. We can’t see the music. Our shit fogs up.” And I was like, “Okay, I get it. I understand.” But it created this weird tension within the music.

And we worked and worked. That’s what bands do. We talked about it, and that was doing livestreams because that’s when we first started playing. We’re like, “We’ve got to play.” Of course, once we started playing it was like having sex again or eating some good food again. “Wow, this is great! I love playing music!” So much fun, those first few porch concerts we did. And it’s still that way. I’ve mostly been doing outdoor gigs and instead of seeing your cellphone looking at you, you’re seeing humans smiling, and you see how important live music is to folks, and that it’s so good for people’s mental health.

Fast forward through the summer, just a few things here or there. We did one big outdoor gig with The Iceman Special July 4th, and I was like, “I’ll do this thing but keep it to 100 people. Make sure everyone wears masks.” Even outdoors. I was like, “They’ve got to keep their mask on or I’m not playing.” And people did. These kids were coming to me, “Mr. Dillon, we heard if we don’t wear our mask you’re going to walk off the stage, so we’re going to keep our mask on.” And it’s pretty funny because I know when I was in my 20s you couldn’t have told me to wear a mask.

It seemed like once people started drinking and hanging out, and if they were on mushrooms or doing whatever psychedelics that are part of the live music experience for a lot of folks, that they’re not going to be worried about social distancing. They’re seeing God, you know? So, I didn’t do another organized, promoted show until probably when they eased some of the restrictions in New Orleans and Texas in October. We were just playing on our porch in Kansas City. In October a bunch of venues were having things outside and that’s when we did some things in October, November. By December, the unemployment got cut off, so we started playing the red states where everything was wide open, and it was harrowing. I told my booking agent to find outdoor gigs, and on all the tours I’ve done, that’s mainly what we’ve been doing. Just one indoor gig here and there. In Denver we did an indoor gig but the place was giant and they only allowed like 70 people in a 500-seat room. So, everyone’s spread out and people kept their mask on. It’s cool.

Other places, like breweries with outdoors patios, were made for this event. The Kessler [Theater] in Dallas, Texas built a stage outdoors. Same thing with Deep Ellum Art Company. Far Out Lounge [and Stage] in Austin. They have an outdoor venue. Last Concert Café [in Houston], same deal. In New Orleans we’ve got the Broad Theater. We started doing shows at this beautiful spot on the Mississippi River that people love, that normally, when it’s low tide, you can walk out. There’s like a football-sized field beach, and we’d set up there and play there. That’s the positive thing of it, as far as playing, is new venues. It’s not stinky old clubs. Of course, I miss some of the old clubs I’ve been playing for 20 or 30 years and those stages of magic but I like playing outdoors. I prefer it. I don’t really want to go back to playing indoors but, of course, we’re going to have to.

JPG: At least you’re playing.

MD: We’re lifers. I’m 55. Everyone I play with, we just have to play. We’re doing it for the music.

3 Comments comments associated with this post

[email protected]

September 9, 2021 at 7:37 pmMuch respect for Mr Dillon, he has always dome his own thing, remained fiercely independent and brings a much need punk rock vibe to our “jam scene”.

Mike Dillon: Suitcase Man – jambands.com – jambands.com – jambands.com – Florida Man News

August 1, 2021 at 10:07 pm[…] Mike Dillon: Suitcase Man – jambands.com – jambands.com jambands.com Article Source […]

Mike Dillon: Suitcase Man – Shyandthefight Musical Instrument Recommendations

August 1, 2021 at 2:56 pm[…] Source link […]