“Sometimes I see the world through Jefe’s eyes, rich in the color of another’s taste

I imagine this world in new degrees, through threads he spins like tapestries; saving the wonder others waste…”

Alan Paul was part of a writing movement that picked up the pieces of music journalism left slightly askew, first by the deaths of giants such as Ralph Gleason (founding editor of Rolling Stone magazine) and Lester Bangs (see Phillip Seymour Hoffman in Almost Famous ), as well as the ambiguous relevance of old-guard critics, such as Robert Christgau, to those then coming of age.

When Paul assumed the Managing Editor position with Guitar World magazine in 1991, it was a third-place music trade in a niche market, with a severely bent crawl towards the mountaintop. Under the leadership of Paul and Editor-in-Chief Brad Tolinski, that peak was mounted within a year. Twenty years, and a Guitar Hero or twelve later, Guitar World’s influence has proven pervasive and deep.

“Sometimes I hear the world through Jefe’s ears, new drums beat in times unknown

I feel the dance grow from his grooves, lured within exotic moves; charming the silk from hearts of stone…”

Paul is a writer who can weave the essence of his subject into the finest patchwork quilt; deftly threading the leather of life well-worn, only to turn simple facts inside out to reveal their true nature- that certain haute couture uniqueness of our favorite artists, delicately woven- like silk lining leather.

“Some days I touch the world through Jefe’s hands, and like a ghost I watch him take my wheel

I lean into his twist and turn, taking what he leaves to learn, making sacred all the things I steal…”

But Paul’s connection to the guitar ran much deeper than whatever writing assignment was next. A devotee of the Allman Brothers Band and the spirit that pervaded that era, Paul ended up taking a series of guitar lessons to supplement his internal encyclopedia of rock, jamband, blues and jazz history. He knew he needed to understand the instrument in a more fundamental way, physically stepping into the shoes of would-be subjects before he could properly do so psychologically.

Developing his musicianship brought added dimension to a form of journalism that once seemed either tiredly doomed, or determinedly set on repeat, in absentia of the fire that made the music worth covering in the first place. While magazines such as Relix, Downbeat and Rolling Stone had always treated music and musicians with a sense of culture and passion, it was heretofore unheard of for a technical magazine to do so.

“Some days I dream the world through Jefe’s songs, lush melodies build into soft refrain

I find the truth within these hymns, of tragic hope and honest sins; haunting is the light that can’t remain…”

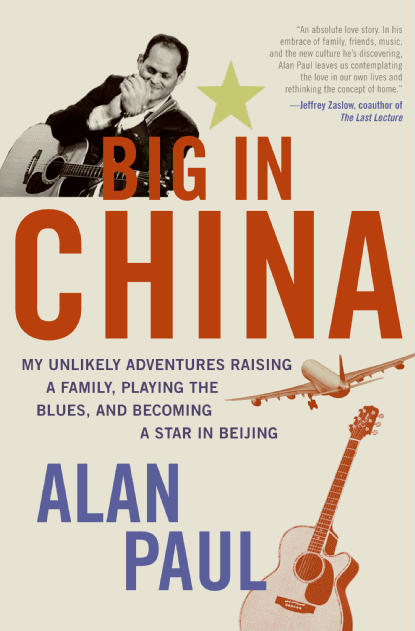

Now, Paul has released a memoir about what became his biggest leap of faith, not only into music, but into the deep end of life itself. The book, Big In China, details his family’s nearly four years spent in Beijing, where Paul first started a personal blog, then a column for the Wall Street Journal, and eventually a band named Woodie Alan, after Paul and fellow guitarist Woodie Wu. The band (also featuring Zhang Yong on bass, drummer Lu Wei, and saxophonist/US Diplomat Dave Loevinger) went on to be named the Best Beijing Band 2008, in a city of twenty-plus million people. Releasing their debut disc, Beijing Blues, as the Paul family returned home to New Jersey, the album, and now Big In China, tells a story that seems at once modern and topical, yet timeless.

“Some days I find my world with Jefe’s help, what’s come before can lead to somewhere new

Live what you love, love what you live, give what you got, take what will give; choosing best fate to rendezvous…” [1]

Much in the same way Paul’s coverage of “old school” musicians brought attention to the overlooked and forgotten, his own journey does the same for certain qualities in our lives that we lose touch with- a sense of adventure, the thrill of testing the unknown, earnestly digging deeper- pragmatically leading by example towards renaissance.

The Literary and the Musical share far too much to ever hope for a succinct summation, but when you encounter a work like Big In China, the two are found so intertwined that one can seem much less without the other. And as Paul embarks on nationwide book tour, which will mix readings and musical performances, he takes his new world blues to a different kind of crossroads- the East/West kind.

Brandon Findlay: The book, at its heart, describes the all-American dream, which, with our current music industry, probably would not happen in America.

Alan Paul: I think at some point- I was writing my column, it started doing well, and the band took off- I was aware of that. I think we were just in the right place at the right time. The opportunity was there to do almost anything that you could think of and pursue. And rather than spend a lot of time thinking about why that was so, I tried to just make things happen as much as I could. There was just this tremendous feeling of optimism and “can-do-anything” [attitude].

There were some specific things that made [the music] unique to China. And there’s more of a music scene in China than people think- I know a lot of people find it surprising that it exists at all. But it is there, and at the same time, it is all-new and still fresh enough that it felt exciting. When we’d come into a town, or play a festival, there were people seeing music like that for the first time. So that gave it an extra edge of excitement. I just tried to feed on it- I was aware of it, but I didn’t dwell on it. I keyed off the energy and tried to take it further.

BF: You mention several times in the book that you maintained a sense of pride in being an American. Is it odd that the American Dream rarely happens domestically, but did happen in China, a country that many Americans are critical of?

AP: Well… yes, it is odd. I don’t know exactly how to answer that, with more depth. One of the things that is exciting about being in China right now, and during that period- and not just China, but other places in Asia- is that they do feel “on the rise”, that there’s a sense of optimism that’s not the case here, which is sad and disturbing.

I think it has a lot to do with our own prioritizing of values in this country. The energy could be changed and turned around and be more optimistic and that, I might say, really has nothing to do with China. I think there’s a little bit of demonizing that goes on with China because people see it growing as we [aren’t]- I think it’s more a matter of the United States re-evaluating it’s priorities.

BF: “Community” is one of the major threads running through the book. You move amongst several communities, with your wife and children being the anchor. Yet, you write that some of your family has not always expressed the strongest faith in your endeavors. You mentioned early in your journalistic career, that family members thought you were “slumming” by covering artists like the Allman Brothers, and your father seemed relieved that you would be “returning to reality” upon your return to the United States.

AP: I never really felt like I was slumming. I know my mother kept waiting for me to get the next job. There were times when I was frustrated with not being able to do some other kinds of writing that I would like to do, to branch out more. It’s just a fact that if you’re writing for Guitar World and Slam, you won’t have the same readership [and] impact with something you write than if you were writing for Rolling Stone and Sports Illustrated. And there were times where that frustrated me. But not really so much because of my ego; it was more that I just wanted to have a larger audience for whatever reason.

But, on the other hand, I had always valued… one thing similar about Guitar World and Slam is that their readers are really passionate, really hard core, and they really care about the subject matter, so I felt like I could write with passion and a certain ‘assumed’ knowledge, not having to explain what an “F chord” is, or what an “alley-oop” is [laughs]. I always appreciated that contact with someone who’s reading this and being impacted by it- that meant a lot to me.

I always felt, to some extent, that maybe having ten readers hanging on everything you wrote, and really being open to it, was better than having a hundred or a thousand people sifting through something you’ve written. But, at the same time, I got to China and met Woodie, and realized that stuff I had written made a difference to him– in a way “opening the door”. If I hadn’t had the Guitar World connection, I may have never had the whole relationship with Woodie, which became so meaningful to me. To some extent, that was a payoff for all my years of loyalty and service and hard work and just really doing stuff I believed in.

My last six months in China, I started working on a book proposal. My column was pretty popular, so I could get peoples’ attention. I had contacted several agents, and one particularly wanted to see a detailed chapter outline, which I started working on. [Then] the Olympics were so busy, the band started doing really well, and I was having so much fun with it, I wasn’t working on this book proposal. I very specifically remember a conversation with my friend Theo Yardley, and I said “You know, for my career, it makes the most sense to spend less time on the band and get this proposal done, because that’s where my career lies in the end, but I’m having so much fun with the band, and I’ll never know if I’ll ever get the chance to something like this again”. And she said, “Well maybe the band will end up being the book”, and to some extent she was right. I feel like I got a payoff for following my gut and my passion.

No Comments comments associated with this post