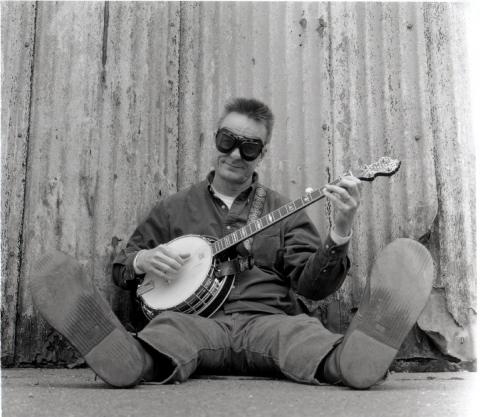

Danny Barnes is a fascinating individual. The Bad Livers co-founder is a banjo player who grew up playing his instrument to Ornette Coleman and Led Zeppelin records. He’s gone on to develop his “folktronics” approach in the live setting which he describes as “a highly processed banjo sound with a lot of loops and atmospheric samples flying around.” In early 2009, while recording on the Dave Matthews Band’s Big Whiskey and the GrooGrux King an invitation from that band’s namesake led to a deal with ATO Records. John Alagia (DMB, John Mayer, Ben Fold Five) produced Pizza Box which ATO released earlier this year. The following conversation offers deep insight into Barnes’ creative process as well as the development of Pizza Box, which Barnes marvels at as “the best record I’ve ever made.” Ladies and gentlemen, Danny Barnes…

I’ve heard that you recently came to a significant conclusion about your musical focus. Can you talk a bit about that?

Well I tell you, I struggled. I didn’t come to this realization ‘til I was 46 or 47. It took a lot of years. I guess part of it was that I have different things that I can do. I’ve always been interested in music since I was a little kid and I’m always researching it and practicing and taking lessons and writing and studying and working, regardless of what’s happening with my career or whatever. I was just kinda ate up with it as they say in Texas but I had different expressions of that. Sometimes I would go and I would help other people make records and then sometimes I would go and be a side person in a band and sometimes I would put a band together and I’d write records and songs and orchestral pieces. I just had a lot of different things that I was doing but I couldn’t figure out how I need to focus my attention.

I didn’t know how I should channel all that creatively. I had friends that were doing things and they seemed to be clear on what they were doing and I wasn’t able to get there. I was always a little frustrated. Finally, I realized just through constantly working, that what I do is I make context, I make ideas and I re-contextualize things and I make things. And so when I realized that, everything got a lot clearer for me because I discovered my raison d’etre. I realized that my job is to make ideas. And it really just streamlined my whole process because I realized that that’s what I’m supposed to be doing, making ideas, making contexts and stuff like that. When I came to that conclusion it just seems like my life got a whole lot cleaner because if something comes up I can go, ‘Is this helping me make ideas or to get my ideas out there or is this not?’ And if it’s not I can just let it fall by the wayside and continue on with what I’m doing.

I realize it’s pretty late in the game to come to that conclusion but just answering that question for myself, why am I here? What am I doing? What’s my purpose here? What is my thing? But when I came to that conclusion, man, it was really great. I was so happy. I still am really happy, because when I get up I know what I’m supposed to be doing.

How does play out in terms of the dynamics between art and commerce?

Well I try to play my ballgame and live with the result. I was watching a basketball game on television and one of the players said that, “I’m just gonna play my game and live with the result.” That’s just kind of what I decided to do. I just play my game and, as far as how it interacts, I think that it’s productive economically because how I get paid is to have ideas.

I think that what I was doing was I got kind of messed up on short term things. Ultimately what I needed to do was kind of step out in faith on what I was led to believe that what my purpose is. It takes a little bit of a while for your navigational direction to adjust and for it to sort of come to fruition because your focus is kind of in a different place.

Would you say that coming to grips with your role manifested itself in the creation of Pizza Box?

I think it was a part of the process but when I finished it, it really put the cap on. It really made sense to me because I just thought, ‘Well, I’m just going to try and write the best batch of songs that I can make.’ I’m around songwriters a lot and a lot of my friends are composers and musicians and directors and stuff like that. So I was working on this batch of songs and I thought, ‘Man I just want to make the best batch that I can get. I want to really work on it.’ And I put a lot of time in it and at that point I was really just focused on writing stuff and I wasn’t really thinking so much contextually or how it fit into any kind of life decision or how it reflected on my life. I worked on that material for about three years, but after a couple years through playing this music for some of my friends, I started getting some good feedback and I started getting excited about it.

It’s almost like when you’ve been at it as long as I have, the process is almost external to your own sort of cognitive thought process. It’s like sometimes when you’re playing, you just look down and your fingers are going crazy and all this music’s flying around and you’re just sort of like letting it happen, you’re not really thinking about it or whatever. It was the same thing with writing. I just looked at it as like an external work and I thought, ‘Man I feel pretty good about this.’ It’s good to be my age, 47, 48 years old and say this is the best record I’ve ever made. I’ve been at this since I was in my 20s and it’s pretty exciting and I think that just sort of helped me to understand that my ideology or my equation of how I was going to make decisions was valid.

No Comments comments associated with this post